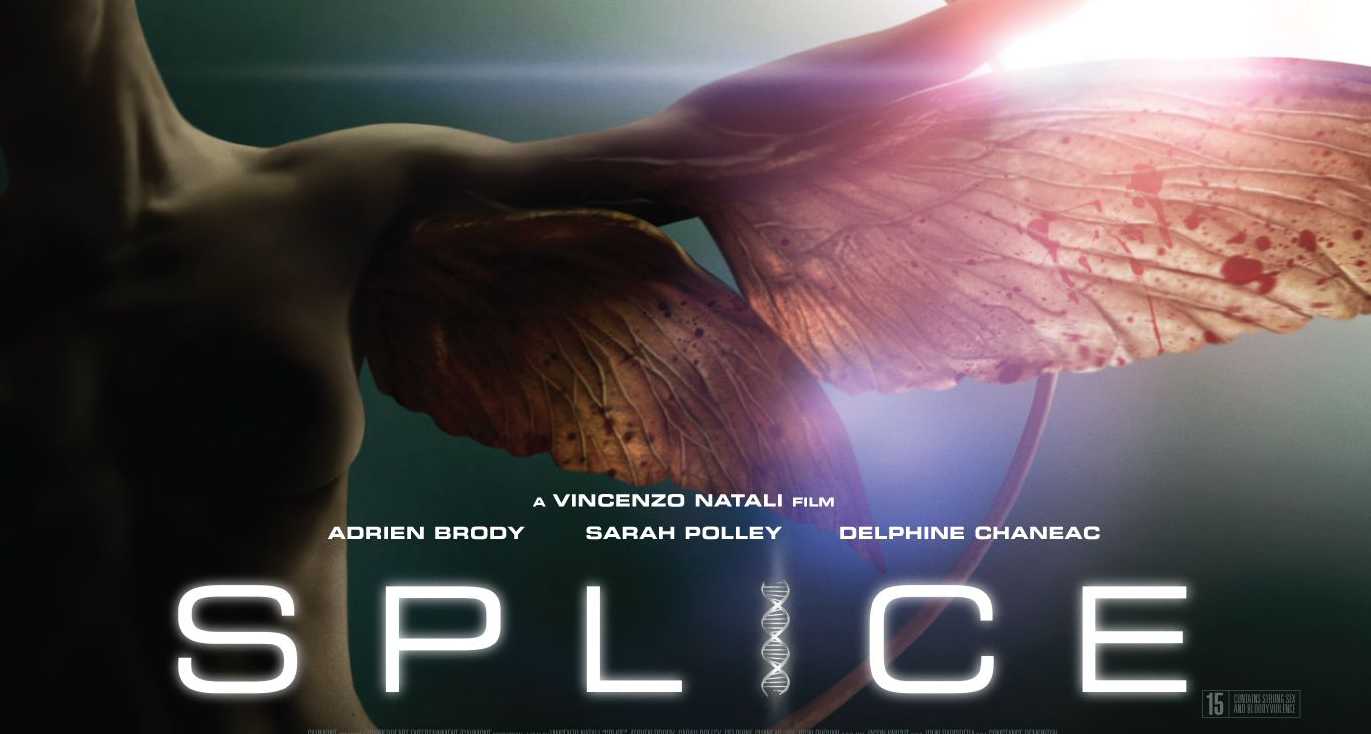

Vincenzo Natali: Splice (2009)

There is virtually no review of Splice (Canada 2009) that does not at some point mention Frankenstein in order to guide viewer expectations of the film and clearly position it within the horror segment. Director Vincenzo Natali himself refers to his film as “a Frankenstein kind of story” (“Behind the Scenes”, DVD release), and the film’s superficial interest in the horrible possibilities of human gene splicing and its resulting creation make it a somewhat predictable creature feature. Taken within the confines of the horror genre, to which it belongs as undoubtedly as Frankenstein does to the Gothic, Splice might not generate much critical acclaim (or academic attention), as did Shelley’s work in her own time.

But let us consider Brian Aldiss’ assumption that Mary Shelley’s text remodeled the traditional Gothic, wrenching its ghosts and monsters away from supernatural origins by establishing a man-made scientific rationale behind the terror (7-39), thus making Frankenstein the first instance of science fiction. Aldiss argues that the “search for a definition of man and his status in the universe” (8, italics in original), is established in Frankenstein as “the first great myth of the Industrial age” (23), and endures to this day in science fiction. Moreover, James Gunn argues that sf, as the “literature of change”, is especially suited to project changes in our evolution and the elusive human condition, calling sf “Darwinian”, the “literature of the human species” (vii). A film that discusses the position of the human when confronted with the next ‘evolutionary step’, that of a genetically engineered posthuman being, might thus open up to a science fictional reading and provide us with a glimpse of our current ‘status in the universe’. Splice is then most accurately understood as a twenty-first century rendering of that great myth, of the creation of life by man.

A Frankenstein Story

The film tells the story of Clive Nicoli (Adrien Brody) and Elsa Kast (Sarah Polley), two young and very successful scientists, and their attempt to genetically engineer the first posthuman by splicing human, animal and plant genes. What to them begins as an intellectual dare (“to see if we can do it”) in a test tube, soon becomes a full-blown illegal experiment resulting in a bioengineered creature named H50, which then develops in burst of mutation from larva via a rodent-like stage, to near-human child and later adolescent. With the development of H50, the scientist become parents, accepting responsibility for their creation and naming her Dren, teaching the posthuman child while at the same time slowly loosing control of the experiment. In the end, the parent-child relation becomes as conflicted as the scientist-experiment relation has been from the start. Clive and Elsa transgress all ethical boundaries both in regards to science and to childrearing, which leads Dren to rebel and in a last metamorphosis change sex to become a violent male posthuman adult, who then goes on to live up to the role of Frankenstein’s monster.

The story works best when it keeps the horror genre in check and foregrounds the science fiction, establishing the metaphorical conceit that all scientific creation, especially the genetic creation of life, resembles parenthood in the sense that it is demanding, frustrating and endlessly bound by respect and responsibility for your creation. But the image of science has changed, the film suggests, from the drab view of the anti-social, slightly odd scientist working in secret and solitude to a media-hyped image of technoscientific glory. Clive and Elsa are hipsters: cool, attractive, dreaming of a designer apartment, Wired Magazine title stories and MTV fame. Clean, well-lighted laboratories have replaced the damp cellars and attics of Frankenstein. Science itself has become a fashionable creative process where tedious and precise lab work takes on the CSI-feel of an action-cut-scene underscored with hip techno music. Teams of young assistants do the legwork and pharmaceutical companies sponsor high-end presentations of the work’s results. The ‘mad scientists’ in Splice are no longer irresponsible because they lost touch with society, have shunned away from friends and family like Victor Frankenstein did because he feared their reactions and was repulsed by his own work. Irresponsibility here is generated rather from opposite forces: In order to function in today’s society, in the attention economy of the internet, in a highly competitive market, scientists have to embrace transgression in order to be one step ahead: “If we don’t use human DNA now, someone else will,” Elsa says and reflects on the loss of both personal as well as commercial recognition.

A Family Affair

The main focus of the story is not on the science though, but rather on the consequences it has on the human condition, exemplified in the scientists come parents, especially in Elsa, the first female to inherit the ‘mad scientist’ role. Preferring the illusion of control implied in a rigorously regimented scientific experiment to the natural chaos that is parenthood, she emotionally rejects a pregnancy of her own, but gets deeply involved in the experiment. When Clive wants to terminate the project, Elsa – in a visually strong and humanizing bonding scene with H50 – ignores all safety protocols and literally becomes its mother, letting it imprint on her. In perfect mimicry of motherhood, Elsa cares for her creation, feels pride in its development and learning achievements, connects with it and becomes a role model. H50, in its more human form named Dren by Elsa, learns as a human child would and develops into a posthuman form, appearing to be an intelligent human girl with animal features. But the threat of the ‘Other’ is inherent in Dren as well: she exhibits a duality of human and non-human features, which the film stresses in visual and auditive opulence through CGI and an eerie soundscape that accompanies all scenes in which Dren interacts. Endearing animal behavior and sweet cooing sounds, somewhere between baby and bunny, are set to counterpoint with threatening gestures, display of predatory traits and aggressive animal noises of hissing and growling. The posthuman is at the same time recognizably human and animal ‘Other’. The film depicts Dren as unstable, not just physically but psychically, morphing not only her body but her identity, shifting from helpless child to threatening predator, from animal to human, from seductive Lolita to monster, crossing species boundaries as well as gender categories, all the while playing on the viewer’s affects of simultaneous sympathy and revulsion. It is her ability of change, of adaptability and instability that unnerves us, that constantly keeps us wary of her posthumanity and that makes her so unlike Frankenstein’s creation which we pity and feel sympathy for explicitly because it is so human. At some point Clive wonders if it is the animal or the human genes that make Dren so dangerous and unforeseeable but the film does not give a straight out answer. Rather, the discussion of science enacting that “great myth”, creating (posthuman) life, is at several times laconically commented upon with the film’s most memorable line: “What’s the worst that could happen?”

Any tempering with DNA, any splice, can lead to unpredictable consequences, the film suggests drastically in a scene, in which Elsa and Clive’s original medical harvest splices ‘Fred’ and ‘Ginger’, two indistinct blobs of biomass, turn against each other. Their genetic make-up incorporates, unbeknownst by their creators, the biological possibility of gender change, and a show and tell for shareholders turns into a bloody massacre when the gender switched Ginger does not mate with but rather fights Fred for male territory dominance. Nature is unpredictable, and the consequences of human tampering are potentially catastrophic and not in the least controllable.

When it went wrong…

Similarly, the question “What’s the worst that could happen?” returns when the scientist-parent Elsa is confronted with the posthuman splice experiment going rogue. When Dren is in a puberty-like phase and rebels against authority, Elsa’s own parental issues re-emerge and she cannot shake those insecurities that kept her from wanting to have a child of her own. Elsa, who has suffered abuse as a child at the hands of her overly controlling mother, enacts an unwilling repetition of that abuse. At first she tries to manage the rebellious teenager with emotional blackmail and threats, and later even resorts to outright physical violence. After a threatening confrontation with the (post-)human child, Elsa determines that the experiment presents with a “disproportionate species identification” and that Dren needs to be de-humanized in order for Elsa to better keep control of her. The brutal transgression fails in this regard though. In the end violence begets violence and abuse begets abuse. Elsa’s desperate act to stay in control triggers the next evolutionary stage in Dren. Similar to Frankenstein’s creature, rejection and cruelty drive her to lash out after the metamorphosis is complete. From then on, about twenty minutes before its end, the film rather randomly loses itself in its creature horror aspects and enacts stereotypical genre moves.

The film’s science fictional aspects though provide ample opportunity for discussion from both posthuman and animal studies. The film’s elaborate metaphor of parenthood provides abundant room for further study. Splice positions the posthuman as a creation of humanity that will always be flawed because it is the child of unfit and irresponsible parents, in regards to both ‘nature’ and ‘nurture’. Nature is unpredictable and chaotic – any attempt to tamper with it, similar to Victor Frankenstein’s hubris, is bound to produce results and consequences that are unforeseeable and impossible to control. But human childrearing, the nurture in the equation and a poignant reversal on Frankenstein, especially interesting in the choice of a female scientist, is equally problematic. How can we, human and anthropocentric, expect to raise the posthuman as human, teaching and measuring its humanity? In this lies a dual hubris, as the posthuman requires a different conceptual position, something to account for the non-human and animal nature of the creation. And it requires us to realize, that our own position is equally flawed, and that the human is, as Michel Foucault has famously argued, a temporary and fading category. The threat of the posthuman, then, lies not only in its otherness, but also in its familiarity.

Works Cited:

Aldiss, Brian W. Billion Year Spree – the True History of Science Fiction. Garden City: Doubleday, 1973.

Gunn, James. “Introduction”. The Road to Science Fiction. Vol. 1: From Gilgamesh to Wells. Ed. James Gunn. Lanham: Scarecrow, 2002. vii-xviii.

Splice. 2009. Dir. Vincenzo Natali. Act. Adrien Brody, Sarah Polley, Delphine Chaneac. DVD. USA. Warner Home Video, 2010.

Citation: Schmeink, Lars. “Splice.” Science Fiction Film and Television 5.1 (2012): 153-57.