Changing the Voices of Science Fiction: The Progressive Fantastic in Germany

The research for this talk was made possible my Leverhulme Professorship at the University of Leeds during the first half of 2022. It was funded by the Leverhulme Trust and hosted by Prof. Dr. Ingo Cornils, Professor of German Studies at LCS Leeds. The lecture was given on several occasions during my time in the UK, among them the following recording from the University of Glasgow, Center for Fantasy and the Fantastic. Here, I provide a link to the video, as well as the transcript and slides for those interested in contemporary German Science Fiction.

Transcript

(longer version than in recording)

When preparing for this talk, I was reminded of the advice that one should always know one’s audience. Thinking about this, I was unsure as to what kind of knowledge about German Science Fiction to expect my audience to have. I mean, some of you might be German studies scholars and students, but how much science fiction will you have encountered during your studies? How much has SF become normalized in the field? Similarly, some of you might be scholars and students of science fiction. And again, I ask myself, how much would you have heard about a German contribution to the field.

The two aspects of this talk, German Studies and Science Fiction Studies, don’t have much overlap. In his book Beyond Tomorrow, my dear colleague Ingo Cornils, explains that „German studies has a blind spot when it comes to speculative literature“ (3) and in the introduction to our new edited collection New Perspectives on Contemporary German Science Fiction, Ingo and I expand this notion from the other side and argue that „German SF does not register prominently in the history of SF either“ (2).

There are several reasons for this „double absence“ (2), as we call it, from the German focus on „Vergangenheitsbewältigung (coming to terms with the past)“ (Cornils 3-4) to the distinction between serious literature and entertainment literature that classifies SF as escapist at best and unreadable trash at worst. And there is a lack of available translations—those interested in science fiction cannot read it, if it isn’t available to them.

So, I want to argue that my job as a Leverhulme Professor working on the transcultural fantastic is to go out and make German SF more known, to promote its values and the import of its message. That is what this talk will do. More specifically, I want you to know about how the genre is currently changing, how it evolves and shapes itself to reflect a more open and diverse German society, how it acknowledges that certain voices have not been heard in German SF and how those voices add to our understanding of what SF can do …

Which brings me to an important issue of contemporary German Science Fiction. And I will shortly need to bring you up to speed about why this new and diverse SF is something worth talking about.

In her book Out of this World, Rachel Cordasco discusses speculative fiction traditions from around the world through the lens of English-language translations. It is fair to say that those authors getting a translation are likely the more known, the more successful, and in a way the more representative of a genre. So, here is the list of authors Cordasco mentions for German SF. Starting with founding father Kurd Lasswitz, and the post-World War II generation of Herbert Franke and Ernst Jünger, she continues in contemporary SF with Wolfgang Jeschke, Andreas Eschbach, Frank Schätzing, and Dietmar Dath.

Unfortunately, I think I see a pattern here. But, you might say, maybe there are biases in translation publishing, not in the genre itself. So, I would add the following names as winners of the Kurd Laßwitz Preis for the best SF novel in German, the most prestigious German literary SF award, voted for by the reading public:

Hans Joachim Alpers, Uwe Post, Tom Hillenbrand, Andreas Brandhorst, and Michael Marrak. Not a lot of diversity there. To be fair, there is one name that I did not mention in the list from Cordasco’s Out of this World, and that is Julie Zeh, whose novel The Method is mentioned shortly. Unfortunately, Julie Zeh is not a genre author, but a novelist that wrote a high literary allegory, a dystopian account of a state run on medical-authoritarianism. All of her other books are not even close to SF.

And then there is Gudrun Pausewang, whose The Wall was the only time ever, that a book by a woman won the Kurd Laßwitz Preis for best novel – in 1988. The one and only time.

So, as you can see, German SF as a community of practice can be quite conservative. And the majority authors that are read as white, cis (and mostly hetero) male, of middle to older age, will not likely be the kind of writers that shake up traditions and depict radical new societies of diversity. They can, and some do, sometimes, in some form. But a gay character here or a woman scientist there do not address the engrained structures or the normative worldview. And to be clear, this is not the fault of any individual one writer. But they benefit from the structures. These authors here are the ones that get translated, get the awards, sell books, and are recognized as German SF authors.

It is obvious that German SF has a diversity issue and does not represent the changing reality of German society, its futures anchored in a world of whiteness, androcentrism, and heteronormativity.

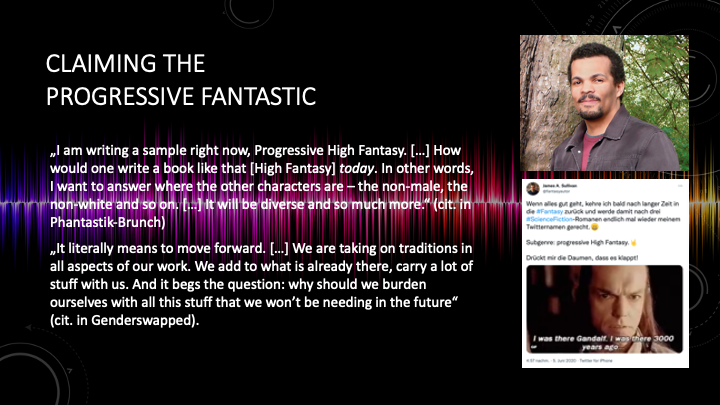

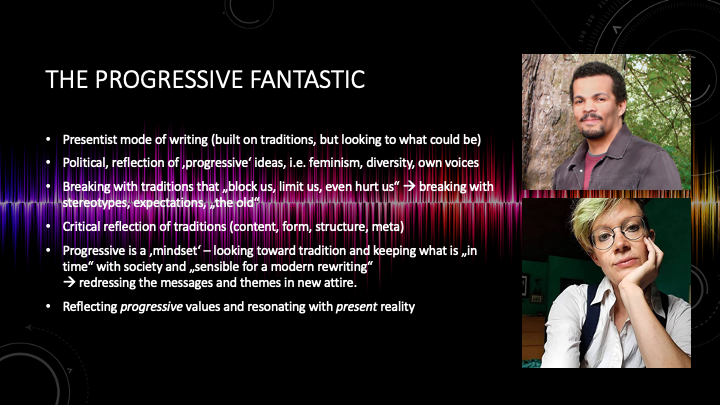

This is where the revolution comes in. And it is a revolution, of sorts. In 2020, when the Black author James Sullivan sent out some tweets about his latest fantasy novels—in Germany the fantastic genres have considerable overlap—he claimed it would be „progressive High Fantasy“ (Sullivan, Twitter). He expanded on the idea by saying he wanted to write a classic Tolkien inspired High Fantasy, but one for today’s world. „In other words, I want to answer where the other characters are—the non-male, the non-white and so on. […] It will be diverse and so much more“ (Phantastik-Brunch). To him, „progressive“ „literally means to move forward. […] We are taking on traditions in all aspects of our work. We add to what is already there, carry a lot of stuff with us. And it begs the question: why should we burden ourselves with all this stuff that we won’t be needing in the future“ (cit. in Genderswapped). The term seemed to resonate so well with other authors that it became the „Progressive Fantastic,“ an umbrella beyond the scope of just one genre.

Together with non-binary author Judith Vogt, Sullivan then wrote an online piece that solidified ideas around the term and called on authors to change their approach to the fantastic. It has become a kind of manifesto and it loosely defines what is meant by a „progressive“ approach. Sullivan and Vogt argue that the fantastic is linked to our imagination of what has „not yet happened“ and „embedded in traditions“. But these traditions can be so entrenched that they are „in the way“ of representing current reality, they can „block us, limit us, or even hurt us.“ Consequently, the progressive fantastic needs to break with these traditions, it wants to promote „progressive [political] concepts such as feminism and diversity“ in order to represent them in narrative worlds. Further, Sullivan and Vogt argue that traditions need to be questioned „on all levels“ and that authors need to „leave behind the obsolete and ill-fitting ones“—that is, critical reflection is a necessary step forward and not just content but also form and structure need to be reexamined. Traditions need to be analyzed for that which still has value in our changing social reality. Sullivan and Vogt further point out: „we need to […] let go of the entrenched and constantly reproduced,“ and break with expectations. The progressive fantastic needs to create narrative worlds that reflect the values of a progressive society, and it needs to resonate with the present reality.

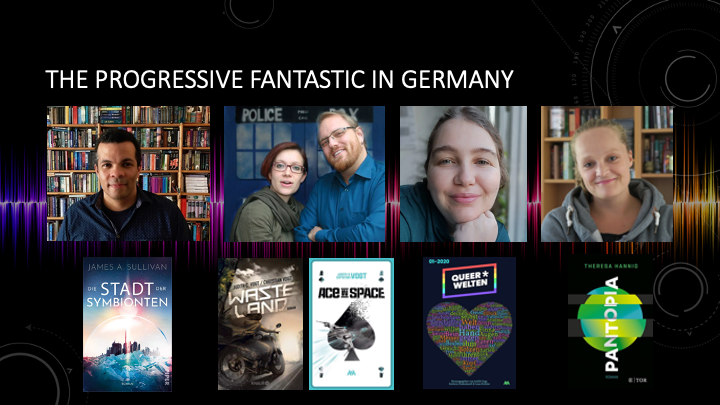

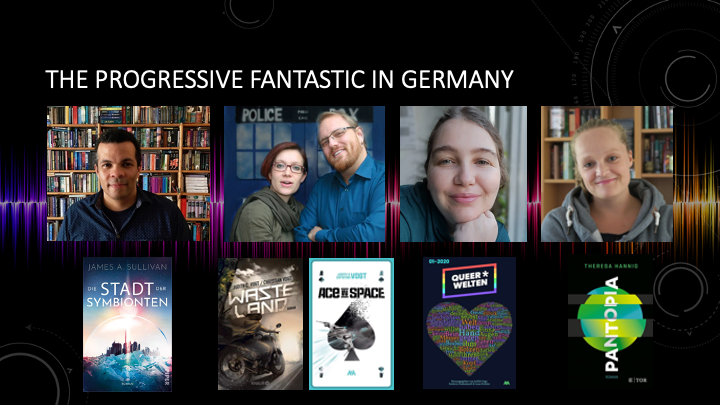

So, instead of going back to traditional German SF, I want to investigate the claims of the progressive fantastic by example of science fiction. I read James Sullivan’s Die Stadt der Symbionten as an Afrofuturist exploration of belonging and of the complexity of living a marginalized life complicit with the oppressors. Judith and Christian Vogt, wife and husband writing team, explore queer linguistics and queer communities in their post-apocalyptic Wasteland and their space opera Ace in Space. Lena Richter discusses issues of (dis)ability and neurodivergence in her short stories „Feuer“ and „3,78 Credit Points“. And lastly Theresa Hannig reinvigorates the forgotten genre of utopia in her latest novel Pantopia.

Systemic Racism and the Diasporic Experience in the Progressive Fantastic

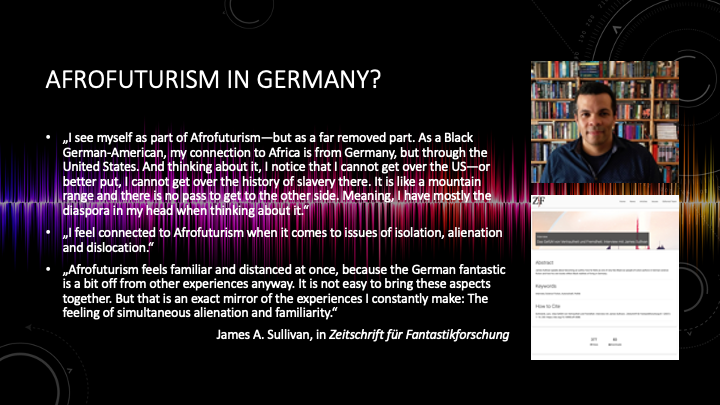

I want to start my journey with the initiator of the progressive fantastic, with James A. Sullivan, whose science fiction novel The City of Symbionts is an interesting reflection on Sullivan’s complicated relation to issues of race and his exploration of Afrofuturism through the prism of his own heritage. In an interview, Sullivan himself explains the complications on how he fits into the mold of Afrofuturism via the detour of his African American heritage. But US history gets in the way, he explains „I cannot get over the US—better put, I cannot get over the history of slavery there. It is like a mountain range and there is no pass to get to the other side.“ Born in the US, Sullivan lived almost his whole life in Germany and thus approaches Afrofuturism via feelings of diaspora, via „issues of isolation, alienation and dislocation.“ These are a reflection of being a Black writer in Germany, „familiar and distanced at once“, „an exact mirror of the experiences I constantly make: The feeling of simultaneous alienation and familiarity.“ It is this unique position of alienation and familiarity, I want to argue, that makes Sullivan’s voice an important part of the progressive fantastic, as it explores issues of race and racism that are largely ignored in German fantastic writing. And it is the connection to Afrofuturism that allows Sullivan to explore the ambiguities of his own diasporic heritage and feelings of belonging to a structurally racist German society.

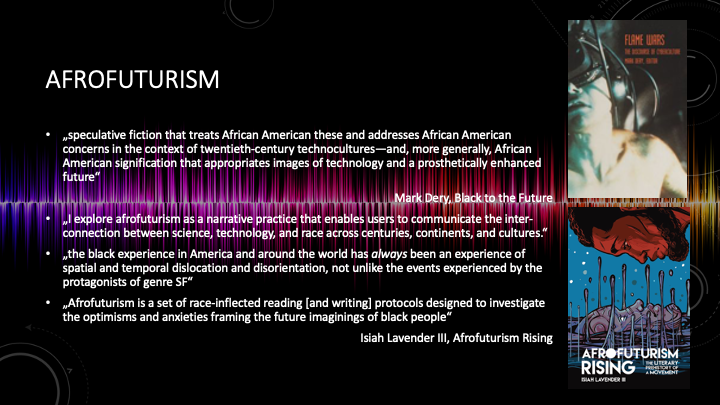

For those unfamiliar, the term Afrofuturism was codified by Mark Dery in 1993 and describes „speculative fiction that treats African American themes and addresses African American concerns in the context of twentieth-century technocultures“ (736). The term has since been broadened, adapted, expanded, and riffed upon, but remains central to the understanding of the relationship between Black cultures and science fiction. Here, I want to use Isiah Lavender’s exploration of Afrofuturism as „a narrative practice that enables users to communicate the interconnection between science, technology, and race across centuries, continents, and cultures“ (2). In his work, Lavender’s central thesis is that „the black experience in America and around the world has always been an experience of spatial and temporal dislocation and disorientation, not unlike the events experienced by the protagonists of genre SF“ (2). In a sense, Lavender argues, that the Black experience is science-fictional and that Afrofuturism is one way to communicate and explore these experiences, it is „a set of race-inflected reading [and writing] protocols designed to investigate the optimisms and anxieties framing the future imaginings of black people“ (2). And James Sullivan’s The City of Symbionts is coded via Afrofuturism to explore a technological future, as much as it negotiates the Black experience of diaspora, and disorientation in a society of oppression.

A short recap and a warning that I will later need to spoil the story to analyze it. Sorry … The city described in the novel is Jaskandris, a refugee city that was founded when alien invaders came to wage war on earth, strip it of all its resources and make slaves of the humans they could find. A last remnant of humanity escaped to the antartica region and founded a city under a shield dome, a city run by powerful AI.

The story follows Gamil, a young and very talented symbiont—a posthuman who has had machinery implanted into his head to be able to communicate with and manipulate all kinds of technology. Gamil follows a signal and at its source finds Nelmura, one of the founders of the city who has been in deep sleep for 500 years and has now awakened because she found out the truth about the intelligences that run the city – they have an agenda, use sleepers as processing power and keep the awake population under control via implanted modules in their symbiotic machinery. Nelmura and Gamil need to free a population that is being oppressed without them knowing—and the whole city is hunting them as terrorists.

Now, Sullivan has in several interviews explained that he does not like including blackness as an explicit marker of race or as reference to his own experiences. Nonetheless, the novel discusses issues of otherness and of oppression. Because of the setting, of alien invaders decimating humanity, the society of Jaskandris can be argued to be post-racial—at least in the sense that no discrimination is passed on people regarding their outward appearance. But since racism is a systemic issue, and one that is linked to what Nicola Lauré al-Samarai and Peggy Piesche call the „structural equipment to dominate, categorize and order the world“, the reader soon notices instances of inequality based on the ability to fully participate in and interact with the city.

There is a marked difference between non-modified humans and the so-called „symbionts“, who have been implanted with what is referred to as „the machinery“. While the AIs run the day-to-day of the city, only the symbionts have the ability to interact with them and the infrastructure on a technological level. Further, they have a second layer of communication, the „thought voice“ which can be used for interpersonal communication while others are present. Both factions are present in the ruling political body, the senat, but the symbionts are the ones controlling the faculties, the intellectual centers that research specific fields of knowledge needed for the city and the AIs. Power structures in the novel do not map easily onto existing categories of oppression, or racism specifically, instead they complicate the notion of hegemonic discourse.

At first glance, it seems that society is divided along the lines of symbionts and non-modified, each group struggling for more political representation. But when Nelmura wakes and reveals that all symbionts are influenced by control modules, the power dynamic shifts. The AIs and those that favor the existing hegemonic structures use the divide of symbionts and non-modified to disseminate false information, throw up smoke screens, and leverage more control and power for themselves.

Sullivan uses the technology of the machinery inside the symbionts as an Afrofuturist metaphor for the complacency and unwitting participation in systems of oppression. The structural equipment of hegemony, the technological infrastructure as much as the mediated social reality, are under the control of the AIs and those that willingly go along with controlling and oppressing the people of the city. With the hegemonic systems in place in the city, Sullivan literalizes what Isiah Lavender refers to „as a dreadfully marginalizing system of thought control in regard to both individuals and societies“. But it is via Afrofuturist tools that Sullivan injects a utopian moment. Lavender argues that the African American experience of chattel slavery (and racist oppression since) led to the creation of Afrofuturist methods of resistance, one of which is the „black ‚networked consciousness‘ […which links] past, present, and future“ through the circuitry of each individual member of the network and „generates hope, a charged impulse representing desire for life, liberty, and knowledge, the essential psychic drive seeding resistance, rebellion and subversive writing“. And it is such „desire [that] charges the emotional register necessary to force social change by technocultural/technospiritual means.“

Sullivan explores this black networked consciousness and the hope impulse by having a black woman, Nelmura, become the network leader, and because she is the founder of a faculty, an archon, she is bringing with her the 500 year-old communal memories and the pain of founding the city. She is also the one providing the tools to literally build a secret communication network. She shares these tools with others, and forces social change by removing the control module from the other’s brains and literally waking them up to the reality of oppression. The „woke“ then form a network, coordinate their efforts by waking other archons from the deep sleep of the system and tapping into their past communal knowledge and memories.

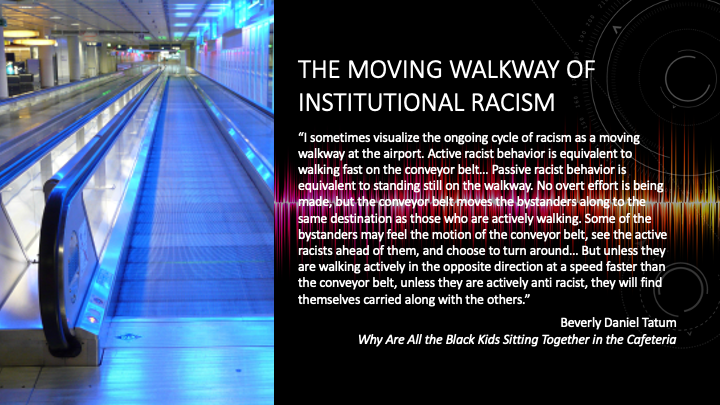

The extended metaphor of the machinery inside the symbionts head might be blunt, but it is effective in communicating the feeling of waking up in your comfortable life to realize that you have been unwittingly complicit in the upholding of control structures, of systems of oppression. It is similar to the idea expressed by Beverly Tatum via the image of the moving walkway of institutional racism which will carry you with it, unless you actively turn around and move against it. Waking up to the movement of the walkway is not enough, you need to do something. Sullivan makes this clear as well, just knowing about the modules does not suffice, you need to actively remove them from your own head – under pressure and against the actions of the system to keep them there.

And this will be the point to spoil the book – so, if you like, just skip this paragraph.

Instead of leaving it at „I did not know, I had a chip in my head that made me overlook oppression“, which to stay with the image of the walkway holds true for white people, Sullivan also wants to point out via Afrofuturist techniques that Black people can be just as unwittingly complicit with the system. At the end of the story, the rebellion against the AIs is successful and the citizens of Jaskandris take back control over their lives, only to realize one central important detail: that they are not really on Earth. That they have been the living computing circuitry of an invading space force of AI mining the galaxy. Unfortunately their ship was shot down in an invasion and the humans were needed to keep the motors running, so to speak. They have been complicit with the invasion, exploitation, and oppression of other species for hundreds of years. Connecting these technological images with ideas of an invasion force, of a middle passage of cargo and humans as computers, is possible to Sullivan by the techniques of Afrofuturism, here literally connecting past, present, and future of Black peoples, revealing to them the painful truth, that they themselves have been complicit in an exploitative system, that there is no escaping from this oppressive system unless you feel solidarity with all. The people of Jaskandris, at the end of the novel, will have to make the decision of how to react, of how to approach the other exploited species that live on their new home world. This is a story, then, that from the perspective of the German SF genre, completely unsettles the status quo, gives voice to marginalized groups and opens a perspective that is uncomfortable for most readers. It is in the best sense of the word a progressive science fiction story, one that makes you move on from where you are.

Non-Heteronormativity in the Progressive Fantastic

Shifting to our next topic. Another aspect that is key to the progressive fantastic is the issue of representation. This is not just true for Black authors or authors of color, but also for women and non-binary authors. And because German is, linguistically speaking, a gendered language, the challenges to finding neutral and non-heteronormative language are high. Progressive fantastic authors Judith and Christian Vogt have been experimenting with ways to make their texts non-heteronormative and have become quite the trailblazers. Before I delve into the details of what they did, I need to shortly explain linguistic features of gender in German, though. And I am not the expert on this, so I hope I don’t mess this up. In general, there are four ways that gender is expressed in language: lexical, social, grammatical, and referential.

- Lexically gendered nouns are those that directly hold the meaning of gendered reference on the semantic level – they refer to persons with a specific gender: man, woman, boy, girl … in German Mann, Frau, Junge, Mädchen

- Similarly on the semantic level, some words have a clearly gendered connotation, a social gender: in English for example „nurse“ which is socially gendered female and needs the marker „male nurse“ to clarify. This does not work in German, because the translation would be Krankenschwester (literally sister for the sick), which not just socially but also lexically genders the term and there is no such thing as a Krankenbruder (brother of the sick).

- Some languages do apply gender on a grammatical level to all nouns and pronouns. German does, using three different grammatical genders: (masculine, feminine and neuter). In reference to persons, German mostly sticks to lexical gender or distinguishes via specific endings: so, der König, die Königin, der Anwalt, die Anwältin … with some exceptions, not quite relevant here.

- And then there is referential gender, which is a pragmatic and interactional category … in German, plural nouns of persons are by default grammatically male, so the list of SF authors (used with a male grammatical form) would include both male and female authors whereas a list of SF authors (used with the female grammatical form) would only include only women. The problem is that referential gender is biased and women are often excluded from plural forms because the ‚generic masculine‘ is used to ‚include‘ women referentially ‚in passing‘ as proponents argue … in practice, the referential gender is male dominant, excluding female reference by default.

And all of this is not even addressing the issue of non-heteronormativity and how language is built on binarisms that completely erase other gender and sexuality expressions. So, it is important to counter this normativity and „the detrimental effects that gender-binary structures may have on people’s perception of their social world“ as queer linguist Heiko Motschenbacher has argued. There are several strategies available, that each generate moments of jarring and thus force readers to actively engage with how gender is created in communication.

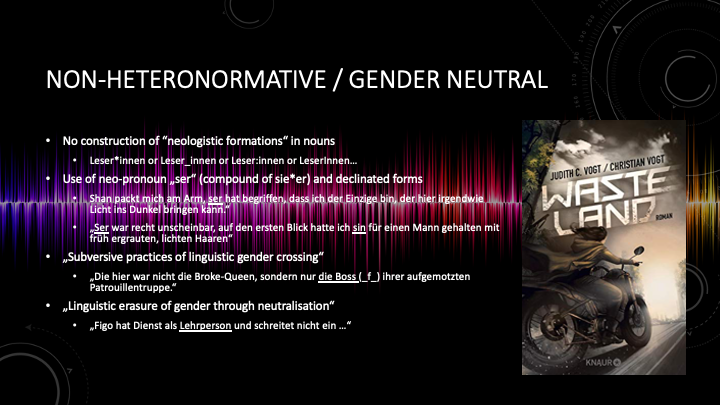

There have been a variety of strategies to create non-heteronormative and gender-neutral phrasing and Judith and Christian Vogt’s 2019 novel Wasteland is the first speculative novel in German that employs a few of them to create non-heteronormative language throughout. There is not a single use of the generic masculine form typically used in German text. They also opt against using „neologistic formations“ for nouns, such as words with special characters that combine male and female grammatical gender or that create a new grammatical gender. But in order to describe a few non-binary characters in the book, Shan and Mo, the authors use the neo-pronoun „ser“, which conflates the German words for she and he. The Vogts further employ what Motschenbacher refers to as „subversive practices of linguistic gender crossing“ in that a term like „boss“ – which is socially, grammatically and referentially gendered masculine – in the novel is used with feminine markers: „This here was not the Broke-Queen, but just the Boss (f) of her ramped up patrol.“ (18) And lastly, they also erase gender linguistically by referring to neutral terms such as „teaching person“ instead of the gendered „teacher.“

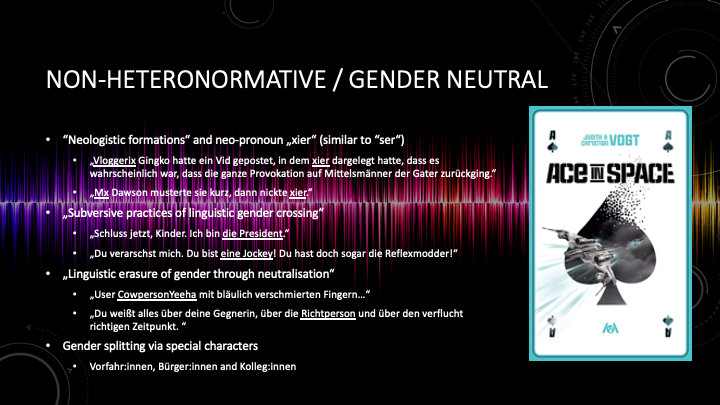

In their next novel, Ace in Space from 2020, Judith and Christian Vogt use a similar queer linguistic repertoire, but change a few strategies, playfully exploring different options and uses. Instead of „ser“, this time they employ the term „xier“ for non-binary characters, which are also more pronounced in the novel, from simple mention to important helper, characters from every walk of life: social media person Gingko, mine worker Noor, pilot Eyegle, judge Dawson. These characters are also described via neologisms and through neutralizing gendered forms. Either neologism such as „Vloggerix“ or „Mx“ are employed, or the epicene term „person“ is used—with gravitas as in „Richtperson“ (meaning judge_n), or light-heartedly as in the online user CowPerson Yeeha. Gender crossing is also more pronounced, and combined with the use of English slang terminology of the space pilots and social media jargon. Terms like „President“ and „Jockey“ which remain English in their German use but are typically gendered masculine (both grammatically and socially) are here used with feminine inflection. In addition, Judith and Christian Vogt even explore the possibility of gender splitting via the use of a colon, as in Vorfahr:innen or Bürger:innen.

The different strategies are employed in the text to playfully highlight that there are several options to eliminate heteronormative language and its use of binarism. Instead, both Wasteland and Ace in Space show that queer linguistics can successfully be used in novels and playfully signal a future that is not dependent on a binary perspective on gender and sex.

The novels do not stop at language, but extend their queer approach into world building through the introduction of queer communities. I refer here to the definition of queer as proposed by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick in her essay collection Tendencies, as „a continuing moment, movement, motive“ that works „across“ categories and is „multiply transitive“ (viii): „the open mesh of possibilities, gaps, overlaps, dissonances and resonances, lapses and excesses of meaning when the constituent elements of anyone’s gender, of anyone’s sexuality aren’t made (or can’t be made) to signify monolithically“ (7). The Vogt’s communities, then, explore queerness by promoting an inclusive approach to any form of personal identity, in the intersectionality of ethnicity, gender, sex, (dis)ability, age, or mental health.

In Wasteland, the authors describe a post-apocalyptic world that is ruled mainly by motorcycle gangs like the Brokes, which favor steep power-structures and a culture of violence and domination and are referred to as „toxxers“. In contrast, the trading community of the „hand-bound market“ is a group of „hopers“, assembled into patchwork families and all sharing values of respect and inclusivity.

Interestingly, the Vogts do not limit their queer approach to the hopers, though these refrain from violence and domination. Yet, both hoper and toxxer communities are shown to be post-racial societies and to be aware of queer non-heteronormativity. Even among the Brokes, oppression of race, sex, gender have been overcome, as one queen refers to her „boys, girls, and enbys“ and the Broke shaman Root recalls meeting another toxxer-emissary pointing out that „as in every conversation in peace times, we asked for his name and pronouns“. That emissary refuses the Broke view of gender and ridicules it. Later, when his lower extremities get amputated and Root thinks „maybe now he will learn that you don’t need a dick to use the pronoun ‚he‘“. The contrast of violence and gender-inclusive worldview here highlights how identity politics and the threat of violence are connected for those in marginalized groups.

The hoper community is similarly inclusive in terms of gender, sex, and race, using pronoun introductions frequently, and including people with neurodivergence and other forms of non-normative physical and mental ability. Zeeto, one of the main characters has bipolar disorder, and because he is a focal character of the narration, his mental state is frequently discussed and made central to the storyline. What differentiates the two communities is their philosophical approach and how they deal with social situations, one favoring domination and competition, the other favoring communality and cooperation. But both hopers and toxxers have understood that identity issues are non-negotiable. No one should assume who and what you are.

In Ace in Space, these communities are shifted, from post-apocalypse to space opera and a world in which space colonization has been driven by capitalist expansion. Consequently, the toxxer worldview is now represented by capitalist conglomerates and a cultish quasi religious gang, while the hoper worldview, though modified by a kind of swashbuckling recklessness, is now embodied in the space fighter gang the Deardevils which are all about swagger and reputation, and a mining colony which tries to stand against the corporation. The attention economy rather than an economy of scarcity defines the parameters of this world. Again, discriminations based on race, gender, sex or ability are eliminated from the groups displayed here, but their representation is not erased. The text takes great care to show that a diversity of characters interact with each other, especially in the Deardevils, which display different ethnicities, physical and mental abilities, genders and sexualities. The society of the future is diverse and inclusive, which is not a position of moral highground, thus not rooted in good vs evil, but a position of common sense.

(Dis)Ability in the Progressive Fantastic

Progressive science fiction thus represents marginalized positions by adopting queer linguistic approaches to language and world building. But as we have just seen in Wasteland, the representation of marginalized groups also extends towards persons with (dis)ability. In the novel, Zeeto is bipolar and the narrative internally focalizes his perspective. Similarly, Ace in Space focalizes a character who is a stutterer, with narrative voice addressing strategies to deal with the social pressure, describing tendencies to avoid certain phonemes and so forth. More than the Vogt’s novels, there is one author in particular that I would like to point to regarding their work on (dis)ability: Lena Richter. Richter has not yet published a novel, but co-edits the fanzine Queer*Welten with Judith Vogt, as well as working on the GenderSwapped podcast with them. In her short stories „Feuer“ and „3,78 LifePoints“, Richter specifically uses science-fictional strategies to focus issues of mental and physical health.

I am reading Richter’s stories through the lens of (dis)ability studies, using Sami Schalk’s definition of (dis)ability with parentheses to indicate a spectrum or „overarching social system of bodily and mental norms that includes ability and disability“ – the importance of the term is its rejection of binarism and, as Schalk argues, „the mutual dependency of disability and ability to define one another“. Richter’s stories explore just that, the shifting definitions of (dis)ability, the markers of health and illness that are culturally defined by social contract and how technologies open or close possible worlds within the range of (dis)ability.

„Feuer“ tells the story of an encounter between teenage boy Tarnik and an Amazon warrior named Cyrix, who is being hunted and needs the boy’s help. The world is post-apocalyptic with remnants of technology and a form of tribal culture. In the beginning of the story, Tarnik explains that he has a condition he calls „the anger“ that makes him lash out at people. It is both a physical and a mental condition, that he cannot control. The words he uses to describe it are negatively connoted, representative of his culture that defines it as a sickness: „The anger in me was a monster with too many tentacles. They strangulated my gut, they let my body shiver with wrath, they balled up my hands into fists and let them lash out against walls and turn over tables. They retched up words from my throat, hateful words, that shot through the room like arrows and found their target in the wounded eyes of my fathers, in the tight-pressed lips of my sister. I did not know how to tame this monster. I could only pick up the pieces after the tentacles had let me out of their grip.“

Even though Tarnik’s family tries to help, there is a stigma around „the anger“, it is seen as „an illness that can befall some people in their young age“ and is in the story associated with puberty – „in just a few weeks, I had grown by a head, my voice had dropped and the anger had awakened in me.“ Cyrix later tells Tarnik that the anger will grow and kill him, if it is not controlled. She also confirms that it is something that most people are ignorant about, that their lack of knowledge is the cause of the social stigma.

During an attack on Cyrix, Tarnik feels helpless to aid the warrior and suddenly realizes the anger is not just empowering him to fight off the pursuer, but also connects him to the Amazon: „The scream … I did not know that I could scream like this, so loud, so full of wrath. All at once I was on my feet and running forwards. I ran, screamed, and hit him in the side. Once more, the tentacles of my anger had taken control. I screamed. And Cyrix answered. I heard my own cry, blending with the cry of the Amazon. For a split second, it felt like I could feel her heartbeat in my chest, hear her thoughts in my head.“

Cyrix explains that the condition is called „the inner fire“ and is an ability that makes the Amazons fierce warriors and connects them in battle. The history of it has been lost, but it sounds like it might be genetic in that everyone can have it them. This is what the pursuer is trying to eradicate. He is called a „renewer of the old world“ and seeks to destroy any form of technologically enhanced being, anything with „implants or abilities“ as Cyrix explains. After they fight off the renewer, Cyrix takes the boy in and is going to teach him to control the fire and become stronger because of it.

The story deals with (dis)ability in that the „anger“ is stigmatized as a threat to the normative majority, leading the renewer to destroy it and the village to ostracize it. Here Richter echoes Margrit Shildrick’s idea that disabled people are alienated from society because of a perceived lack in the status of subjectivity. The „valued attributes of personhood are autonomy, agency—which includes both a grasp of rationality and control over one’s own body—and a clear distinction between self and other,“ Shildrick argues, thus „any compromise of mental or physical organization or stability“ results in „a deep-seated anxiety.“ Tarnik’s inability to control the anger, to lash out at his family, produce anxiety about a loss of subjectivity in those witnessing the anger. But Cyrix intervention redefines the anger as the inner fire, claims a different embodied reality and thus is, in a sense, a cripping. Cripping, like queering, challenges what Robert McRuer has called „compulsory able-bodiedness“ and seeks to understand „the relations of visibility“ that surround the different terms. Cyrix makes visible the embodied difference of those with the inner fire, claiming subjectivity not despite of her difference, but because of it.

Picking up the idea of embodied difference of (dis)ability, in „3,78 Lifepoints“ Richter denies the empowering moment of claiming crip. Instead, the story shows how the genre of science fiction usually renders invisible disabled bodies by providing technological solutions to what is essentially framed as a problem. As Kathryn Allan has pointed out, SF usually sees disability as „as a physical or mental impairment that is supplanted through the application of technology, transforming the disabled body into a figure of prosthetic awe and medicalized prowess.“ In the story, Richter denies this erasure and instead exposes the „the illusions of inviolability and self-mastery over the body“ that technologized crip narratives uphold.

In the story, the non-binary character Amii gets a job delivering a package to a specified location. As the story opens, their „SeroTone-device“ stops working, as they soon find out, because the social security office has flagged Amii as being uncooperative. Without it Amii is unable to mentally process all of the sensory overload that the fully mediated cyberpunk world presents—they get overwhelmed by lights, sounds, and motion: „Videos and Gifs in screaming colors, cute animations of animals, thin bodies jumping up and down in front of a mirror. Everything moves, is too colorful, too bright, too much. Normally I only notice this at the edge of my consciousness, but the disruption of my implant has pushed my brain into the normality of this way too fast.“

Already at this point, Richter links Amii’s (dis)ability with their ability to work and to perform in the capitalist system. As McRuer argues, this is a main point of the „compulsory nature of able-bodiedness: in the emergent industrial capitalist system, free to sell one’s labor but not free to do anything else effectively meant free to have an able body but not particularly free to have anything else.“ The story makes this explicit by having Amii remember a school teacher saying that through prosthetic technology, (dis)ability such as blindness could be eliminated: „Problems such as this are problems of the past, the woman on the screen had said. I remember how she continued: By now, everyone could work to earn a set of artificial eye replacements in case of a loss of vision.“

As it turns out, though, able-bodiedness is a necessity to work in the oppressive capitalist system. Because of Amii’s cognitive disability, they neglect to comply with the social security office, which resulted in the device being disconnected. Amii does not own the device outright but is granted it as (dis)ability aid to help them perform a job. The disconnect in turn impacts their ability to work – a feedback loop they cannot break out of: „Without the implant, it is possible to work, but grueling. Without the implant, I do not manage 60 hours per week, I do not get highest level evaluations for friendly demeanor. Without those evaluations I will never succeed in any of the applications I constantly put out. For real jobs, permanent jobs with access to all health care services.“

Amii’s whole existence is centered around making enough LifePoints to warrant better services, to move along the projected axis of normative behavior. But the events of the day throw them back to their own cognitive impairment. What becomes clear in the story, through the narrative perspective of Amii’s position, is that Amii’s disability is a social construction. Sensory overload is produced through the capitalist need for accumulation and thus advertising. The pressure to work 60 hours a week and always be superficially nice is socially constructed because society persists in its „compulsory able-bodiedness“ and the need to define norms of behavior.

What both short stories thus show is that (dis)ability is defined against social and cultural parameters and that we need (dis)abled voices to understand how people with (dis)ability are denied subjectivity and what needs to change. „3,78 LifePoints“ highlights that the neoliberal capitalist system we are in will provide technological solutions to perceived problems, thus erasing and ultimately entrenching (dis)ability as a marker for otherness. „Feuer“, on the other hand, shows it might work to change the cultural perception of what constitutes embodiment, thus accepting the whole spectrum of (dis)abled bodies as human.

The Utopian Form and Tradition in the Progressive Fantastic

For my last example, I want to explore shortly the progressive fantastic’s claim to put even generic traditions to the test and reevaluate the larger structures of the fantastic. The genre that seems most interesting to test traditions seems to me utopian literature, especially given that most utopian texts in the last few decades have been dystopian. As Ingo Cornils has pointed out, German science fiction of recent years tends towards literature as „dark mirrors“ of society, seeing „the dystopian form as the ideal vehicle to explore the social and psychological consequences of scientific and technological progress. However, in its seemingly inexorable move toward the (post-)apocalyptic, and in its appetite for bleak nihilism, it risks jettisoning the joyful celebration of human potential and losing its capacity to generate the “awe and wonder” associated with imaginative SF of the Golden Age.“ Cornils warns that too much dystopia will eventually „yield diminishing returns“ and leave audiences without hope for a better future. German SF, so the summary position, has been traditionally too dark to produce the „principle of hope“ as Ernst Bloch has famously called utopian dreaming.

In her novel Pantopia, Theresa Hannig leaves behind German nihilism for the principle of hope, exploring the positive change necessary for us to solve the climate catastrophe as well as the rampant social inequality that plagues our twenty-first century society. The utopian future of the novel sees the creation of global state based on the principles of the human rights charta, which grants certain rights to every human being on earth, but extends this to include AI as well – a necessity as a strong AI is the creative mind behind the world state Pantopia. For Pantopia, certain principles exist: everyone can become a member and be granted the same rights. Pantopia is pacifist and sets saving the planet from destruction as its primary goal. Individual freedoms are curtailed by the principles of the common – meaning you can do what you like unless it contradicts the principles of equality, pacifism, or ecological conservatism. Everyone will receive a universal basic income, but in return everyone will become participant in the Pantopian economic system which is built not on current capitalist markets but adjusted to include the world price of commodities, which taxes any behavior that is in contradiction to Pantopia’s principles – if you destroy the environment that destruction is priced into the commodity, if you pay lower than living wage, that is taxed, and so forth. And lastly, all policy is fully transparent and all members of Pantopia have voting rights in its discussion and implementation – a direct democracy made possible by technology.

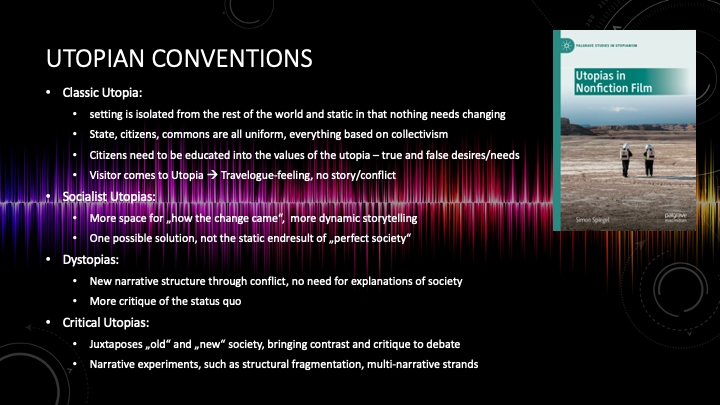

But for the purpose of this talk, I am not interested in the utopian world itself, but rather in the narrative and generic traditions that Hannig addresses and reevaluates in-line with the ideals of the progressive fantastic. In his book, Utopias in Nonfiction Film, Simon Spiegel has an excellent chapter on the generic conventions of utopia, which I am basing my analysis on. Spiegel points out that genres are historical and change over time with use and thus finds different conventions for the classical utopias, socialist utopias, dystopias, or critical utopias. According to Spiegel, utopias classically described isolated societies set apart from the world. They are static without much need for change. Their societies are built on conformity and uniformity, leaving no margin for deviance. As such, their citizens need to be made for utopia, educated in their values. And narratively, most utopias are pretty boring, reading more like a travelogue, highlighting descriptions of policy and infrastructure instead of action or characters. Over time, these parameters changed, as utopias shifted from geographically apart to set in a future, or by allowing more dynamic stories. With the 20th century came the shift to the dystopian, which concentrates on conflict generated by deviant beliefs and is generally negative. This is the mode that to this day still dominates utopian writing. Not even the critical utopias of the 1970s really changed that. In these there are usually two societies set to contrast each other, thus highlighting the different paths forward. Overall the main function of utopia remains true, that it is a critique of current society or what Thomas Schölderle claims is a „critical diagnosis of the times“.

So, first off, Hannig rejects the dystopian mode outright, having herself written two dystopian novels before, this novel reclaims positive and hopeful visions of the future for the progressive fantastic – it is one of the „green shoots“ of hope that Cornils identifies in his writing. Set in Germany, the story takes place in the near-future, thus rejecting the distance and isolation used in utopian fiction. Here, we realize that Hannig is aiming to stress the social function of utopia as critical diagnosis. She returns to what Spiegel calls the classic utopian „two-world structure“, the old world whose function is to lay open the critique, and the new world that explores a „will to improve“ pointing out that a different path is possible. But in removing isolation and distance, Hannig allows readers to clearly identify one of the worlds as their own. In this, Pantopia is like Utopia, the novel, itself – part of a ‘threshold genre,’ characterised by a ‘double encoding […] as both fiction and nonfiction, literature and nonliterature’. Pantopia, then, is as Spiegel claims for Morus, „despite its narrative-fictional framework, […] in some respects closer to a philosophical tract or a political manifesto.“ What I mean by this is that Pantopia can be read as a political treatise that points out existing solutions to our problems, be they social inequality or the climate catastrophe. The only science-fictional novum in the novel is Einbug, the AI that implements all of the already existing solutions. As such, Pantopia (similar to Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future) functions as a „Serious counterproposal: […a fictional work] at least partly conceived as serious political programmes“ – Hannig wants people to take the political alternatives in Pantopia seriously.

In connection to this political goal of implementation, there is another structural element that Hannig changes. As Spiegel points out, since utopia already achieved a stable policy, the conflict of how to get there is never addressed. But since Hannig is explicitly interested to provide current readers with a counterproposal to the way things are, she focuses her novel especially on „the emergence of the utopian state–the phase before utopian order is fully established“. In the novel, we witness the status quo and how Einbug becomes an emergent AI. Einbug realizes the need for intervention and then sets in motion a slurry of actions, such as gathering money, securing his servers in Antartica to be out of national reach, and building a model island in the Mediterranean to convince citizens to join the World State. Einbug also calculates all of the ways that nation states and the political, industrial and media elites will fight against the Pantopian world republic. In this, we see another deviation from utopian traditions, a tip of the hat to the dystopian mode instead, Hannig focuses on the conflict between the two systems, enacts the resistance to the utopian state and explores how such a utopia would deal with deviance as much as how the old, false system will deal with the establishing of another, true system.

As we can see then, Hannig has taken the progressive fantastic’s notion to heart to reevaluate not just the traditions of narrative and content that are entrenched in the fantastic genres, but here purposefully turns on the structural program of utopian writing. Instead of showing the reader the ‚better place‘ Hannig explores the messy part of „how we got there“ and thus makes it even more explicit that change is possible, that all the options we need to enact a utopian system are already at our grasp.

To conclude, then, I hope to have shown that in the German fantastic genres, a shift has occurred, and a new mindset has taken root that sees the genres not as bastions of traditions but as fields of experiment. The progressive fantastic, as loosely claimed as it is, opens the genre up to the experiences of marginalized groups, it allows description of the alienation of BIPoC authors in the white majority society of Germany, it playfully explores the notion of inclusivity and diversity in communities of non-heteronormativity, it makes room for the challenges and new perspectives of people with (dis)ability, and it reevaluates the notions of generic structures to inject hopeful blueprints of a better world into our life worlds.

The texts I have chosen to discuss are examples from science fiction and from a small group of authors that have been at the forefront of the progressive fantastic. But there are more … authors and texts that are myth, gothic, urban fantasy, young adult, high fantasy, or genre blending. I was already pushing the limits of this talk, so please do explore widely what the German fantastic has to offer, here are some starting points for your journey. Thank you.

Bibliography

- Cameron, Deborah. Verbal Hygiene. Routledge, 1995.

- Feenberg, Andrew. Transforming Technology: A Critical Theory Revisited. Oxford Univ. Press, 2010.

- Genderswapped Podcast. „Progressiver Weltenbau: Im Gespräch mit James Sullivan,“ Podcast, ep. 25, Aug 01, 2020. https://genderswapped-podcast.podigee.io/34-episode-25.

- Hellinger, Marlis. „Empfehlungen für einen geschlechtergerechten Sprachgebrauch im Deutschen.“ Adam, Eva und die Sprache: Beiträge zur Geschlechterforschung, ed. By Karin M. Eichhoff-Cyrus. Bibliographisches Institut, 2014, pp. 275-291.

- Hirschfeld, Magnus. Die Homosexualität des Mannes und des Weibes. Louis Marcus Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1914.

- Hollinger, Veronica. „(Re)Reading Queerly: Science Fiction, Feminism, and the Defamiliarization of Gender“. Science Fiction Studies, Bd. 26, Nr. 1, 1999, S. 23–40.

- —. „Something Like a Fiction: Speculative Intersections of Sexuality and Technology“. Queer Universes: Sexualities in Science Fiction, herausgegeben von Wendy G. Pearson u. a., Liverpool University Press, 2008, S. 140–60.

- Jagose, Annamarie. Queer Theory: an introduction. New York Univ. Press, 2010.

- Latham, Rob, u. a. „SFS Symposium: Sexuality in Science Fiction“. Science Fiction Studies, Bd. 36, Nr. 3, 2009, S. 384–403.

- Melzer, Patricia. Alien Constructions: Science Fiction and Feminist Thought. First edition, University of Texas Press, 2006.

- Motschenbacher, Heiko. „Grammatical Gender as a Challenge for Language Policy: The (Im)Possibility of Non-Heteronormative Language Use in German versus English“. Language Policy, vol. 13, no. 3, 2014, pp. 243–61. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-013-9300-0.

- Motschenbacher, Heiko, und Martin Stegu. „Queer Linguistic approaches to discourse“. Discourse & Society, Bd. 24, Nr. 5, 2013, S. 519–35, https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926513486069.

- Olderdissen, Christine. Genderleicht: Wie Sprache für alle elegant gelingt. Duden, 2021.

- Pearson, Wendy. „Alien Cryptographies: The View from Queer“. Science Fiction Studies, Bd. 26, Nr. 1, 1999, S. 1–22.

- —. „Science Fiction and Queer Theory“. The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction, herausgegeben von Edward James und Farah Mendlesohn, 1. Aufl., Cambridge University Press, 2003, S. 149–60. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1017/CCOL0521816262.011.

- —. „Towards a Queer Genealogy of SF“. Queer Universes: Sexualities in Science Fiction, ed. by Wendy G. Pearson, Veronica Hollinger, Joan Gordon. Liverpool University Press, 2008, S. 72–100.

- Pearson, Wendy G., Veronica Hollinger, and Joan Gordon (eds.). Queer Universes: Sexualities in Science Fiction. Liverpool University Press, 2008.

- Phantastik-Brunch, „Progressive Phantastik.“ Podcast, ep. 12, Jun 14, 2020. https://anchor.fm/phantastikbrunch/episodes/Progressive-Phantastik—Der-Phantastik-Brunch-Folge-12-efdesu/a-a2fa433.

- Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Tendencies. Routledge, 1994.

- Sullivan, James A. „Bald ist es soweit!“ Twitter, @fantasyautor, Apr 02, 2020. https://twitter.com/fantasyautor/status/1377985132469096449.

- Sullivan, James A. „Wenn alles gut geht“ Twitter, @fantasyautor, Jun 05, 2020. https://twitter.com/fantasyautor/status/1268934876776083456.

- Sullivan, James A., and Judith Vogt. „Lasst uns Progressive Phantastik schreiben!“ Tor-Online, Aug 16, 2020. https://www.tor-online.de/feature/buch/2020/08/lasst-uns-progressive-phantastik-schreiben/.

- Weinstone, Ann. „Science Fiction as a Young Person’s First Queer Theory“. Science Fiction Studies, Bd. 26, Nr. 1, 1999, S. 41–48.

- Yaszek, Lisa, und Patrick B. Sharp, Herausgeber. Sisters of Tomorrow: The First Women of Science Fiction. Wesleyan University Press, 2016.