Frankenstein’s Offspring: Practicing Science and Parenthood in Natali’s Splice

This essay reflects on the mythopoetic rewriting of the Frankenstein myth in Vincenzo Natali’s film Splice (2009). In adapting the story to 21st century context, the film shifts the original story of science gone wrong and its consequences on the human body into the contemporary form of biohorror, of science gone right, but with unforeseen and transgressive results. The film thus concentrates on the discussion of the moral dimension and societal consequences of creating a human-animal hybrid by means of a central allegory of science as parenthood. The posthuman creation becomes the basis for discussions of scientific accountability and responsibility, the illusions of control over scientific progress and the ethical considerations involved in all contemporary technoscience, but genetic engineering most specifically. In the film, the monstrous becomes allegory for the challenging concepts of love, caring and parenthood when faced with the possibility of gene splicing and the hubris of a posthuman potential. Moreover, scientific involvement with consumer capitalism is revealed to complicate the already shifting ethical bases of science, as the biopolitical understanding of life as commodity exerts dominance in the working reality of scientist.

In ‘Biohorror/Biotech’ Eugene Thacker distinguishes the traditional form of body horror, which he links to Gothic works such as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) as a narrative of science gone awfully wrong, from a contemporary technoscientific version he refers to as biohorror, arguing that in this form science has gone awfully right: ‘biohorror suggests that the monsters and abjections of technoscience are the product of a set of techniques and technologies that simply work too well’ (113f.). Whereas Shelley discusses Victor Frankenstein’s failed moral values and descent into madness and elicits horror from the human body threatened by science, biohorror uses the ‘synergy between the biological and technical domains’ to move beyond the limits of the body and create an ‘effortless un-doing and refiguring of the body’s boundaries’ (114). As one of the most influential cultural depictions of body horror, Frankenstein has provided the seed for an ever-changing, modern myth continually reshaped into different cultural and historical moments. Frankenstein’s madness, scientific hubris and complete ignorance of ethical standards have become part of the cultural imagination and response to the radical scientific insights and social developments of the Industrial Revolution. Carol Dougherty acknowledges an idea by Clifford Geertz, when she argues that myths have a double function: ‘myths provide a common body of material that is not only important to think about but also “good to think with”’ (13). Within Shelley’s narrative one finds the mythical building blocks that have been reshaped into biohorror to explore 21st century technoscientific progress and questions of posthumanism.

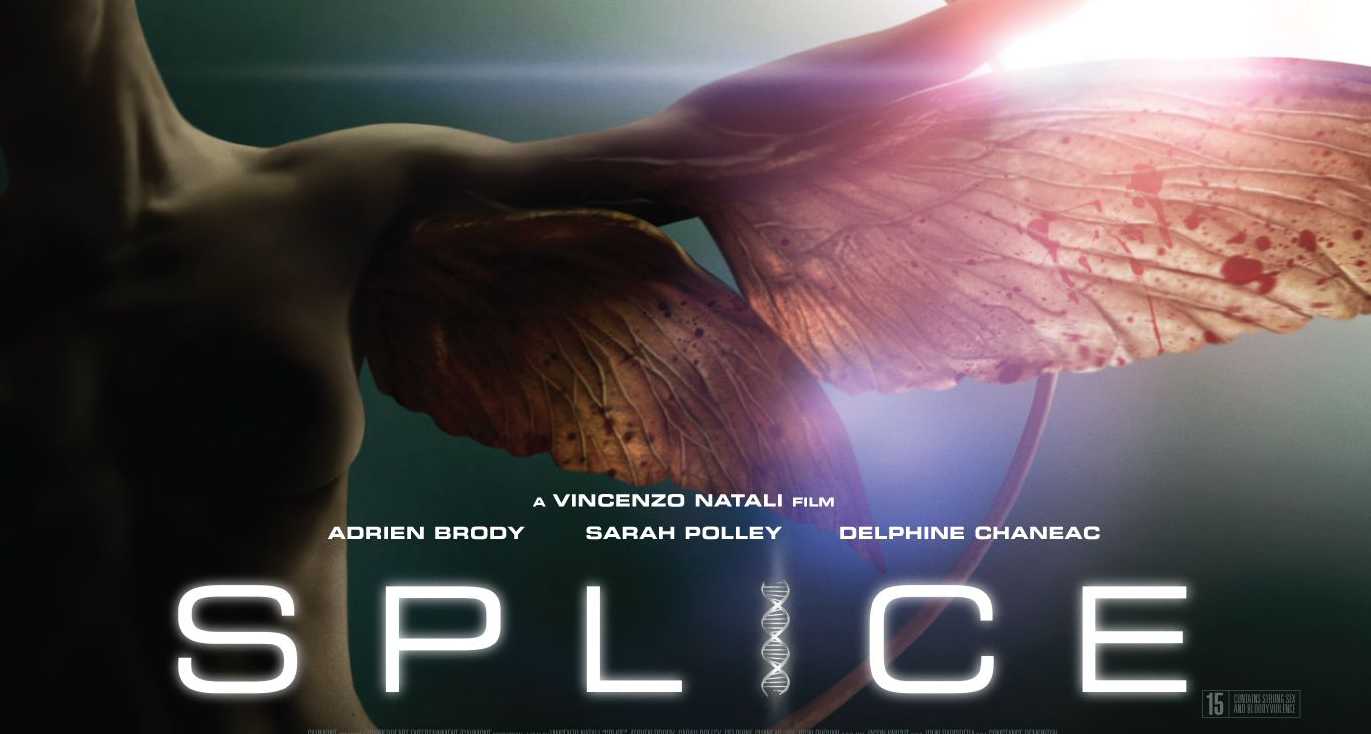

One recent example of the modern Frankenstein myth – the mad scientist at work, playing god and creating another being – is Vincenzo Natali’s 2009 film Splice (Canada/France/US), a film that makes use of the original’s body horror template and shifts the mythology into biohorror. Its form needs to be understood not as a divergence from the original source material, but rather through Chris Baldick’s contention that the ‘series of adaptations, allusions, accretions, analogues, parodies, and plain misreadings which follows upon Mary Shelley’s novel is not just a supplementary component of the myth; it is the myth’ (4). Reading the film as mythopoeisis allows us to investigate what happens to its ideological content when an author uses the existing ‘host of associations, connotations, and interpretive baggage’ (Dougherty 13) that surrounds the myth and reinterprets it according to the cultural needs specific to its contemporary audience. [LS1]

That Splice is an adaptation of the Frankenstein myth is so obvious that there is virtually no review of the film that does not at some point mention the connection, as does Natali himself in interviews and commentaries:

I think that Splice fundamentally is a creature movie for adults because it pays homage to all the things that one would expect from a Frankenstein kind of story but it deals with aspects of the relationship that the creators and their creation have, that I think most movies don’t ever deal with. [LS2]

In an interview with sftv.com Natali strengthens the bond with Frankenstein when he admits that the ‘emotional quotient’ (Captain) of the story is what fascinated him about Frankenstein myth in the first place. Splice, Natali says, ‘hopefully breaks new ground … with the emotional relationship with the creature to a degree that we haven’t seen outside of Mary Shelley’s original novel’. Interpreting Shelley’s story as dealing with familial issues, Natali concentrates on the father/son relationship, downplaying other aspects such as the creature’s origin in death (Baldick 3), the self-duplication of the creator (Small 15), or the romantic heroism of the artist/creator (Haynes 94).[1]

Before beginning the analysis, a short summary of the film might be in order: Splice tells the story of two genetic engineers, who are also a couple, and their experiment of creating a human-animal hybrid through DNA re-sequencing. Clive (Adrian Brody) and Elsa (Sarah Polley) then raise their creation in the lab, while hiding her from their employers. Dren (played first by Abigaile Chu, later by Delphine Chanéac), the creature, evolves and grows through mutation, at some point becoming uncontrollable in the lab environment. Clive and Elsa secretly move Dren to an old farmhouse and become more and more conflicted about the ethical implications of the experiment, shattering their own relationship in the process. When Dren rebels against her captivity, Elsa’s own abusive childhood resurfaces and a struggle erupts in which Dren is mutilated and traumatised. The film concludes with Dren evolving/mutating one more time, shifting biological sex from female to male and becoming predatory, killing Clive and impregnating Elsa before being killed in turn.

The film takes the Frankenstein myth and adapts it to 21st century context, incorporating pervasive media, gene splicing, global capitalism and a precarious human condition. Furthermore, as Natali has stated, it uses the familial aspects of the myth to explore parallels in the relation between creature and creator, child and parent, posthuman and human. In what follows, I will explore the film’s evocation of aspects of the Frankenstein myth as an allegory for parenthood and the burden of childrearing.

Parents

Clive and Elsa are not entirely modelled on Victor Frankenstein, ‘the sine qua non of the Mad Scientist’, (37) as Glenn Scott Allen calls him, but the resemblance is telling. Their similarity is easily recognisable in their ruthless drive for scientific progress and their hubris in the creation of life. Frankenstein is obsessed with a desire to ‘penetrate into the recesses of nature and show how she works in her hiding-places’ (Shelley 46). He is convinced he will be able to master life by studying death and goes beyond any consideration for natural order, committing a serious ‘breach of ethics with regard to the self/other relation’ (Ku 120) to achieve his goals. His methods succeed, but he also pays a price for his hubris, in that his act of idealistic creation turns destructive and uncontrollable:

Frankenstein’s horror begins at the precise moment when the creature opens its eye, the moment when for the first time Frankenstein himself is no longer in control of his experiment. His creation is now autonomous and cannot be uncreated any more than the results of scientific research can be unlearned, or the contents of Pandora’s box recaptured. Hence, paradoxically, it is at the moment of his anticipated triumph that Frankenstein qua scientist first realizes his inadequacy. (Haynes 97)

Frankenstein’s work is born out of misplaced ambition and a singular desire for scientific progress. His creation emerges, then, not from love for and community with the creature but from Frankenstein’s madness, his thirst for glory.

Similarly, Clive and Elsa are originally not motivated to create life out of love but as a means to gain (academic) fame and glory. When pitching their proposal for splicing human DNA into a new hybrid creature, Elsa argues, that they are practically gift-wrapping ‘the medical breakthrough of the century’ for their employer, that they will be able to cure an array of severe illnesses such as Parkinson’s, diabetes and even cancer. Confronted with the objection that policy and public opinion would not allow such research, Elsa coolly replies: ‘If we don’t use human DNA now, someone else will’. When the CEO, Joan Chordot (Simona Maicanescu), still refuses, Elsa and Clive decide they will not work as practical engineers (i.e., finding applications for their research) but will remain engaged in transformative experimentation. The scientific legwork is not attractive to them, and thus they ignore ethical concerns or public moral outrage, breaching codes of sanctioned behaviour. Granted, the film explicates their moral struggle, revealing their concerns about their decisions and their personal and professional insecurities when first attempts fail, but in the end their ambitions win and they take the step from modelling to full organism: ‘We just need to find out if we can generate a sustainable embryo. Then we destroy it. Nobody will ever know’. Similar to Frankenstein, Splice enacts the violence and uncontrollability of the creation and ends in the destruction of (at least one of) its creators.

Allen claims inaptitude in all social graces is one of the key criteria for the scientist as ‘Wicked Wizard’ in the popular imagination; here, Clive and Elsa differ from the original Frankenstein mythology. Where Victor is anti-social, reclusive and cannot muster interest in anything but his scientific endeavour, Clive and Elsa resemble geeks or nerds who inhabit their own subculture (cf. Feineman) and can thus be regarded as role models to some extent (i.e. through the favourable portrayal of intellectual women; cf. Inness). Both Clive and Elsa are young, attractive and immersed in pop-culture. Clive especially carries the air of ‘arrested adolescence’ (‘Splice, the Twisted Family’) and seems well-versed in geeky subculture, demonstrated by his wardrobe (his t-shirts, for example, usually represent scientific puns) and tastes in music (technoid ‘fascist Uber-Music’) and interior design (a giant manga poster hangs above their bed and a Marvin figurine from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (1979–1992) adorns their living room). Elsa on the other hand desires a more mature style (represented by the envied designer apartment in minimal chic), but is nonetheless still embedded in geek culture (evident in her bright pink camouflage t-shirt and her addiction to ‘Nerd’ candy). Although they are never shown to have social engagements and do focus all their energy on their work as a vehicle for personal as well as professional status, they are far more sociable than the reclusive Victor Frankenstein. They work with a small team of scientists for a multinational biotech corporation, have a project manager and give interviews and stockholder presentations. Their work is featured on the cover of technoscientific hipster outlet Wired Magazine, where they hand out what Elsa sardonically calls ‘bumpersticker wisdom’: ‘If god did not want us to explore his domain, why did he give us the map?’ Their demeanour is thus more in line with that of a subcultural in-group than that of the recluse Frankenstein. Clive and Elsa live the culturally immersed lifestyles of musicians, independent filmmakers or fashion bloggers – in fact, Clive even maintains his own Twitter account (#CliveNicoli) and personal blog site (www.nerd-lab.com). Natali argues that scientists today are not the clichés of ‘typical Hollywood’ fare, ‘which is remote and robotic’ (Captain) but rather the opposite. After spending time with geneticists, he realised: ‘Genetics is a young person’s business. The mean age of the scientists that I saw was around 30. Very erudite, smart, pop-culture savvy, very bright and very passionate’.

Clive and Elsa undermine the classical image in terms of familial ties, most noticeably in conforming to a hetero-normative relationship. Frankenstein’s madness is a symbolic representation of his retreat from family relations. Shelley used Frankenstein to remind Enlightenment thinking of its own limitation and the negative consequences of ignoring human contact and emotions. Instead of focusing on the (feminised) family space, Victor chooses the (masculinised) space of science, ignoring natural order and causing him to lose his grasp on reality (cf. Allen 255). Frankenstein therefore represents the prototypical mad scientist, who sacrifices his chance at natural reproduction for unnatural creation, which according to Daniel Dinello is a deeply gendered transgression against natural order: ‘The mad scientist, who took over the divine role of creation from God and the natural role of creation from woman, gets punished with death’ (42f.) Thus Victor’s maleness is also complicit with a gender-based image of science in general: ‘the master narrative of science has always been told in sexual terms. It represents knowledge, innovation, and even perception as masculine, while nature, the passive object of exploration, is described as feminine’ (Attebery 134).

Clive and Elsa, by contrast, are in a stimulating, functioning and socially validated relationship, working within their small team, even with family because Clive’s brother is one of the lab assistants. The film subverts gendered roles: Elsa appears to be far more driven by self-interest and scientific hubris than Clive; the female CEO of Newstead Pharma functions as metonymic signifier for capitalism, exploitative science, and consumer society; and Clive is shown as a caring, protective and emotionally attached parent. This inversion of the relational dynamic, as Natali points out, is a conscious choice: Splice discusses ‘a Mother/Daughter relationship’ that is complicated by the aspect of sexuality when the film ‘becomes a bizarre love triangle’ (Captain). Through the inversion of the relational matrix and the subversion of gender roles, Splice stresses creation and the responsibility of parenthood as the main problematic of the Frankenstein myth.

In the opening scene, the film projects the images of a birth from the perspective of the newborn. We first see Clive and Elsa via a subjective camera emerging from darkness to extreme light, then shifting to the fisheye view of the creature. The laboratory and the team of scientists are shown in cold blue-white tones, camera movement is erratic and its focus pulses to the accompanying sound of a heartbeat. During the first minutes, the creature painfully struggles to life, the camera repeatedly fading to black, the image losing focus and colour as the creature drifts out of ‘consciousness’. The electric shocks to jolt it back to life are represented by violent shaking motions, flashes of light and images of the scientists working frantically over the creature’s POV shots. The scene ends with Clive and Elsa placing the creature in an incubator, removing their masks and smiling down on their ‘child’. The attitude of proud parents markedly announces the gender role inversion: Elsa coldly and scientifically states: ‘No physical discrepancies’, allowing herself only a faint smile. Clive, on the other hand, grins widely and emotionally announces: ‘It’s perfect!’ The viewer is placed in the position of the creation, the newborn, which seems to be only precariously alive. Clearly the scene tries to build sympathy with the scientists, marking them as parents struggling for the survival of their child. Genetic splicing mythopoetically replaces pregnancy and childbirth, and the ethics of scientific conduct must merge with the ethics of childrearing.

Dren’s conception simultaneously subverts and confirms the Frankenstein myth by portraying science itself as fashionable and its practice as lifeless. On the one hand, the creational act becomes a culturally hip process where tedious and precise lab work takes on a CSI-feel of an action-cut-scene underscored with techno music and finding the right mix for the splice is reminiscent of ‘pulling an all-nighter’ at college with your buddies – Asian food in paper containers and sleep deprivation worn as a badge of honour. On the other hand, the secluded damp cellars, dark attics and charnel houses that brought forth Frankenstein’s creation find their equivalent in the similarly secluded Gothic architectures of postmodern technoscience. The genetic laboratories, built into exchangeable boxes of indistinguishable industrial parks somewhere in suburban New England, are similarly devoid of life and loom with dark potential. Their clean-tiled examination rooms and glass walls, computers and biotech machinery, are simply modernised versions of Frankenstein’s haunts – their literal coldness and metaphorical emotional detachment ‘betokened by the ice-blue tones of Tetsuo Nagata’s photography’ (Romney).

Dren’s birth scene is similar to the birth scene in Kenneth Branagh’s Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (US/Japan 1994). Both present images of womb-like sacks, artificial containers that serve to bring the creature to life that are filled with amniotic fluid. In each, the final step across the threshold of life violently shatters the birth container in an eruptive explosion spilling the fluid, similar to the discharge before natural human birth. An even stronger parallel frames Dren’s artificial birth with a natural birth disrupted by complication. Elsa’s attempt to manually induce labour, reminiscent of an assisted birthing of a calf when Elsa reaches into the artificial womb with her arm, prompts the unborn creature to latch on to her physically, sharing its agony through her arm and eliciting screams from her that are a reminder of women’s pain during birth. Clive, at first the panicked and confused father, opens the birth container to let out the amniotic fluid, shatters the glass and then cuts the womb sack. The creature, in a strong visual metaphor, is still attached to the umbilical cord from which it violently rips free. The messiness, the pain, the screams and the violent transition into life, as well the clinical atmosphere of the room and equipment, provide a strong connection to hospitalised childbirth. The posthuman birth, metaphorically displayed here, does not go smoothly; the transition into life is violent and irreversible. The two geneticists have thus become the first posthuman parents and are now facing a singular form of parenthood. [2]

Elsa and Clive are not ideal parents, just as Frankenstein never was. Victor abandons both his artificial creation with ‘breathless horror and disgust’ (Shelley 55) the minute he sees its hulking body and his own natural (and yet unborn) offspring several times when he postpones marriage with Elizabeth. His abandonment of Elizabeth suggests a rejection of family ties and natural fatherhood, but his abandonment of his scientific creation weighs more heavily as he displays a complete lack of sympathy with the helpless creature by refusing ‘sustained guidance, influence, pity and support’ (Hustis 845). Not providing mentorship and a moral compass to his creature is probably the most ‘outrageous transgression in the light of human beings’ ethical responsibility to and for other species’, (120f.) as Ku rightly argues, and thus exemplifies Victor Frankenstein’s monstrosity as a parent.

The responsibility of a parent to his child is at the heart of Shelley’s novel but has often been excised from adaptions in favour of making the creature an uncontrollable, evil ‘monster’, as did early stage versions in the 19th century and most filmic representations in the 20th century. The recent London National Theatre production of Frankenstein by Danny Boyle (director) and Nick Dear (playwright) seems to negate exactly this moral judgment of the ‘monster’, instead dealing with, as the play’s program booklet suggests, ‘urgent concerns of scientific responsibility, parental neglect, cognitive development and the nature of good and evil’ (Dear, back cover). As such, the play introduces a scene not original to Shelley’s text, in which Victor’s inhumanity and denial of responsibility are offset by Elizabeth’s compassion and moral outrage. ‘I’d never abandon a child’, she exclaims to the creature and when confronted with Victor’s actions, she promises to change him, to make him see his errors: ‘He must learn that he has to take responsibility for his actions, and that – … and that we must always stand up for the disadvantaged’ (Dear 70). With Elizabeth at his side, Victor might have been a better parent, and the nuclear family, the play seems to suggest, represents the natural order of child rearing. Yet the scene ends in irony, as the creature is not disadvantaged any longer and has ‘at the feet of my master … learnt the highest of human skills, the skill no other creature owns: I finally learnt how to lie’ (Dear 71). Killing the only ‘perfect’ human being (because of her innocence and compassion) he has ever met, he completes his lesson and thus destroys Victor’s chance to have that nuclear family.

Splice, similarly, conflates the topics of scientific responsibility and parental neglect into a discussion of personal and professional ethics. Elsa is driven to see her work come to term, forcing Clive’s cooperation and persuading him to ignore the ‘moral considerations’ of illegal human DNA splicing for the greater good of helping humanity defeat disease, ignoring safety protocols as well as ethical problems several times during the film. When Clive wants to abort the experiment, showing empathy for the creature (‘Do you think it is in pain? … It’s not formed right’.), Elsa argues in scientific terms that they can learn more, get data on ‘sustainability’.

Else makes it very clear, though, that she is not ready to have a child through natural procreation or to accept the responsibility that goes with it: ‘I don’t want to bend my life to some third party that does not even exist yet’. ‘What’s the worst that could happen?’ Clive asks, and Elsa avoids the question, which emerges again later in the film, a running gag on both parenting and the scientific endeavours. Jonathan Romney points out in his review:

The film is very funny in its dark jokes about parenthood and the horrible dawning realisations that come with the job: that babies are very noisy, demand endless attention and totally mess up your work habits. The funniest line – ‘We’re biochemists, we can handle this’ – could speak for the delusion of all new parents that no small, helpless creature could possibly be that hard to manage.

Elsa’s rejection of natural parenthood is based in her suffering massive abuse at the hands of an overly controlling and yet powerless parent. She strongly resents the power relations of the parent-child dynamic as well as the underlying issue of the controllability of the child. Therefore, she prefers the rigorously regimented scientific experiment, which she believes give her power and which turns out to be an illusion. When confronted with the second stage of Dren’s evolution, following her gestation as a slug-like entity, Elsa cannot bring herself to terminate the experiment, instead making contact with the more mammalian creature. After Clive gets her out of the room, she fights with him about the creature’s fate. Clive wants to terminate the experiment and kill the creature, but Elsa is more emotionally attached than she would like to admit: ‘We can’t do that! Look at it!’, she exclaims and sedates Dren instead, once more hiding behind scientific curiosity as a motivation to keep the experiment running. The scene ends with a cross-cut among the creature’s slow struggle against the gas, its helpless bouncing around the room—falling to the floor and breathing laboriously—and an extreme close-up on Elsa’s emotional reaction, shot from behind, angled so as to reveal her in partial profile on the right edge of the screen before a black background, glancing coldly but intensely at the creature and at last swallowing her discomfort with the situation. Both editing and composition suggests Elsa’s attempt to detach herself from emotional responsibility for the creature– which is later revealed to be her biological offspring (she used her own DNA for the splice). Polley’s acting in this scene is minimalistic, showing strong emotional restraint and thus revealing Elsa’s failed attempt at distancing. Scientific distance and neutrality, the film seems to suggest, becomes impossible when the experiment is fraud with personal issues, compromised moral values and the biological-evolutionary scope of creating a new species of posthuman beings.

Frankenstein’s rejected father/son relationship is turned on its head in Splice, as Elsa’s parental attachments kick in when she is confronted with her creation. Her bonding with it confuses her scientific rationale and erases any neutral ground on which to make ethical decisions. She cannot bring herself to abandon the ‘child’ as she realises her responsibility for the creature’s helpless and vulnerable state of being. Elsa and Clive also have another responsibility to consider, however, that of the corporation for which they work. Newstead has a vested interest in the genetically engineered posthuman creation and wants to assert its property rights. Here, the film shifts from body horror to biohorror. Thacker argues that one of the central themes of biohorror is that the body becomes productive biological machine and the owning corporation can ‘capitaliz[e] on the body as raw biological material for future profits (gene patenting, genetic drugs, in vitra fertilisation)’ (120). Further, the body is instrumentalised not simply as raw biomass but is ‘strategic[ally] contextualized’ towards specific commodifying functions, ‘e.g. the production of desired proteins’ (120).

The bodies of Fred and Ginger,[3] Clive and Elsa’s original but non-human spliced organisms, immediately come to mind: their sole function is their ‘ability to produce medicinal proteins for livestock’, leading the company to its decision to isolate the genes responsible so as to manufacture these proteins industrially. In effect, the raw materials of life (in the sense of zoe, all life) become commodities that the corporation owns and controls. When the Fred and Ginger experiment fails, Newstead forces the scientists to abandon splicing and concentrate on the protein synthesis that will yield marketable products. Elsa suggests that they might start over and recreate the splices, but Joan harshly rejects her: ‘No more monsters! We don’t have time for that. We need the gene that produces CD-356. And we need it now!’ In the original script, the scene is longer and even more explicit. Elsa admits that their progress on the protein has been slow, which brings about another angry remark from Joan, clearly pointing out her superior position: ‘Then you’re not allocating your resources effectively’ – after this, she demotes Clive and Elsa and allows corporate bureaucrat William Barlow (David Hewlett) to be ‘hands-on in charge’ (Natali et al. 67). The scientific experiment is thus under strong pressures of corporate control, needing to produce results under any and all circumstances – solid scientific groundwork, space for the possibility of setbacks, ethical supervision and a secure work environment are lacking as the parent company pushes for profit.

This sets up the disturbing question of how strongly the child becomes instrumentalised as well in the contexts of the film’s conflation of research and parenthood, revealing how much pressure there is to create the ‘right kind’ of child – one that is productive for hegemonic culture – when Newstead finds out about Dren, and Barlow demands to see ‘it’, making clear the corporate position that ‘it doesn’t belong to you’. In the script, the technoscientific instrumentalisation of Dren’s life is even more pronounced, when Barlow argues that the splice is ‘company property’ (Natali et al. 104). The parents reaction to their child being treated as simple commodity which Newstead intends to analyse for potential profits strikingly reveals their complicity in the process: ‘“It” doesn’t belong to anyone’, Clive states defiantly, not noticing the irony. He himself has only shortly before declared his and Elsa’s responsibility at an end, wanting the scientific study to conclude. And Elsa has willingly and violently abused Dren’s DNA to synthesise the desired protein for her pharmaceutical financiers, which alerted Barlow’s to the human-animal hybrid in the first place.

Splice projects this corporate instrumentalisation of zoe even further, as the final scene of the film suggests. The film now sets up the allegorical conflation of science and parenthood as literal instead. Elsa will become mother once again, this time not by creating life in a test tube but instead by carrying to term the child conceived with the male Dren. The epilogue shows how corporate capitalism finds a use for the situation: Joan is pleased with the results of the experiment, stating that Dren was ‘filled with a variety of completely unique compounds’, marking Dren’s (dead) body simply as a receptacle holding corporate products to be mined. ‘We will be filing patents for years’, Joan says, smiling contently. Moreover, the scene suggests the deep complicity of the scientist in the process of corporate technological instrumentalisation: Elsa continues her scientific hubris by agreeing (she is not forced) to carry her baby to term. Joan performs her CEO duties, stating that the company is ‘extremely excited, that you are willing to take us to the next stage. Especially in light of the … um … personal risk’, but she seems to have her doubts. After Elsa gets up, the camera lingers on her pregnant belly before showing both women in silhouette against the bright but grey light from outside the office. The next cut shows Joan in a medium-to-close shot looking over her left shoulder, tracing Elsa’s movements. She seems to ponder the situation, glancing at the contract on the table in front of her before rising as well.

The film closes with Joan approaching Elsa from behind, her voice soft and more personal than before: ‘Nobody would blame you if you didn’t do this. You could just put an end to it and walk away’. The shot is focused on Elsa by the window, Joan standing behind her, unable to see her face. Elsa smiles sadly to herself, then repeats once more ‘What’s the worst that could happen?’ Joan seems touched, closing the distance between scientist and corporate financier, placing her hands on Elsa’s shoulders. The final image is of Elsa embraced by Joan in a gesture reminiscent of Elsa’s family photographs, a mother providing nurture and security to her emotionally insecure child. This image is suggestive of a corporate mother surrogate taking care of and responsibility for Elsa, who with her signature has become a valued asset, if not a corporate product herself. Yet the image is problematic, as the symbolism as well as the cinematography suggest: the two figures appear blackened and without contours, unreal against the bright, contrasting light from the outside world, while the camera slowly moves away, withdrawing from the human gesture and instead revealing them against the cold, practical interior of the office. The film thus evokes distrust in the corporate mother’s love, leaving open the question of whether corporate care can replace a biological mother’s affection. The fact that the original photograph projects a false image, as Elsa’s relation to her mother was hollow and abusive, underscores the potential of a similar abuse – no real responsibility for the child (beyond the corporate interest) and no loving familial nurture may ever exist.

Offspring

After having examined the parental figures, we now turn to the offspring and the challenges faced in its upbringing, once more drawing parallels between the Frankenstein myth and this contemporary reimagining. The first and major difference lies in how the posthuman beings come to life. While Frankenstein tried to find the ‘elixir of life’ (Shelley 39) he contradictorily used dead matter, observing ‘the natural decay and corruption of the human body’ (49), even torturing the ‘living animal to animate the lifeless clay’ (52). Frankenstein’s creature, built from cadavers and sewn together to be bigger and stronger than man, is horrifying and repulsive to all who see him. In Nick Dear’s play, we are given an explanation for the reaction that the creature evokes (in the stage directions): ‘He is made in the image of a man, as if by an amateur god. All the parts are there, but the neurological pathways are unorthodox, the muscular movements odd, the body and brain uncoordinated’ (4). The creature’s repulsiveness lies in the uncanny: he is physically close to the human but oddly and recognisably different, especially his skin and eyes (‘yellow skin’, ‘shriveled complexion’, ‘dull yellow eye’, ‘the watery eyes’ (Shelly 55)). His connection to death and decay separates him from humanity and prompts Frankenstein to describe him as ‘the demoniacal corpse to which I had so miserably given life’ (56).

The creature (only named Dren later in the film when she develops a human appearance) is created from the building blocks of biological life, her DNA a composite of human, animal and plant DNA. Dren is not stitched together and re-animated from dead bodies but born into life from a single blank ovum injected with spliced DNA. She needs to develop from single cell to fully-grown organism – a process that is helped along by modern medical science, including a birthing chamber with amniotic fluid and strict pre-natal monitoring. Dren is thus a monstrous product of both nature and technoscience, throwing into crisis all categories (cf. Cohen 6): she is born/made, cultural/natural, human/animal/plant, male/female. Over the course of the film, this monstrous state of categorical crisis is enacted as a series of challenges to scientific process and the similar struggle of parenthood.

When the splice is born, it is still a larva in a protective flesh-cocoon, a mass of flesh similar to Ginger and Fred but with two symmetrical skin flaps at its ‘head’ and a long muscular tail that has a stinger. The bite marks on Elsa’s arm after the violent birth suggest a maw of some kind but it is never explicitly shown. Elsa’s allergic convulsions after being bitten further suggest the presence of some form of poison. Clive traps the larva and administers epinephrine before cradling Elsa, the image of him holding her evoking childbirth – Elsa’s hair is sweaty, her skin bloodless and she slowly recovers from great physical exertion. A close-up of their faces reveals that the freshly minted parents are not serenely happy but shocked and horrified at their creation: ‘What was that?’, Elsa asks numbed, and Clive responds ‘A mistake’. The scene echoes Frankenstein’s horror and rejection of his own ‘miserable monster’. In the next scene, Clive and Elsa’s faces betray guilt, insecurity, fear and repulsion. From this larva stage on, the splice develops through different ‘mutations’ in evolutionary bursts – drastic physical reactions inherent to its protean ability that manifest when the creature is confronted with new environmental challenges.

When Elsa and Clive try to kill the creature after the initial phase of the experiment, they discover the larva cocoon empty and believe the creature is dead. In fact it has metamorphosised into another form, a transformation omitted from visual depiction, representing the splice as unpredictable child, with abilities beyond its parent’s expectations. This change reveals the creature’s potential to become a threat. The first encounter with the next stage of the splice’s development (a bird-rodent-like creature) is presented as uncanny – both frightening and familiar. The scene begins with a typical horror scenario: Elsa hears something in the lab, signalling for help, but Clive in the control room does not notice her. In a rapid succession of cuts between close-ups of the frantically breathing Elsa and her point-of-view shots, curtailed by the gas mask she is wearing, the film orchestrates a surprise moment when we see the splice hanging from the ceiling, Elsa turning to face it. A fast cut brings us face-to-face with the creature opening its maw (filmed in an extreme close-up) and screeching, before it chases through the lab, jumping over equipment and leaving a wake of chaos. Editing and mise-en-scène indicate that we are to read this as an encounter with the monstrous, with the non-human Other.

Then the scene shifts. The splice hides behind a container, first seen as just a shadow, then slowly emerging from the protective cover, whiskers and snout visible. It squeaks, more threatened than threatening, and Elsa’s mothering instincts take over. She ignores safety protocols, shedding the protective gear of gas mask and gloves to thwart Clive’s plan to gas the room. She kneels down, bringing her closer to eye-level with the creature, and tries to bond with the splice based on empathy for its fear and pain in this situation. A slow-paced, low angle shot of Elsa kneeling and extending her hand, followed by a close-up of the splice emerging from its hiding spot change the fast-paced action scene into an intimate moment of mother-child bonding, or as Elsa calls it ‘imprinting’. The encounter of both species is visually presented as a dialogue: first an establishing shot of both from the side, in which Elsa remains still and the splice jumps forward, advancing towards Elsa’s hand. Then a shot-reverse shot sequence of Elsa observing the splice and the splice feeling Elsa with its whiskers, all of the shots slightly tilted to account for difference in height but slowly tracking in to signal the lessening of distance between them. This intimacy breaks up when Clive comes into the room, out of focus behind Elsa, to drag her out while keeping the creature at bay with a broomstick. This sequence is filmed from the creature’s perspective, camera focus changing to acknowledge Clive above Elsa’s shoulder and then opening to a wider and higher shot in a fixed position just above the splice’s eye level of the two figures retreating, before cutting to a zoom out away from the creature, while the door closes into the frame, leaving the camera in darkness.

Just as important as the visual cues that recognise the subjectivity of the creature (by changing to its perspective and incorporating it in a conversational shot) is sound design of the latter part of the scene. On the one hand, the creature can be heard cooing and warbling while it is bonding with Elsa – ranging from animal noises like sniffing, clicking and chirping to more vocalised sounds like bird calls or ones similar to those of a human infant. These sounds create affection for the creature, eliciting feelings of sympathy as we realise that it is hurt, frightened and helpless. The animal/child-noises are designed to emphasise the community of non-human and human in a scene strongly reminiscent of mother-child bonding or the care of young animals, as well as to provide a feeling of familiarity with the creature. When Clive moves into the room and the splice feels threatened, though, the soundscape shifts dramatically to snarling, growling and hissing. These sounds combined with the creature’s defensive gestures, such as a display of jaws, crouching attack position and prominent stinger movement, shift the atmosphere once more back to horror but this time our sympathies are divided. It is Clive who acts in a threatening manner, disturbing the familial scene between Elsa and the splice. Clive is the intruder and the splice’s reaction seems normal, justified. The long dolly-out away from the scared creature, screeching once more in confusion, and the door blackening the screen leave us emotionally sympathetic with the splice.

The scene evokes a strong emotional bond early in the scientific experiment (as well as in parenthood), but it also cinematically suggests the potential for the monstrous Other in the child. Clive and Elsa are challenged in their notions of a controlled experiment, their need for secrecy, for example, outweighing proper protocols, and their emotional attachments complicating decisions. Just like parents, their minds are far from scientifically rational where the creature is concerned. When the creature’s human side begins to show, Elsa names her Dren and starts to teach her as a mother would a human child, thus strongly contrasting with Frankenstein’s choice of abandonment and neglect.

Frankenstein’s creature, crafted stronger and bigger than an adult human, has no need to physically adapt through phases of growth, but it does need to grow mentally and learn what it means to be human. Thus when Frankenstein casts out his creature, he abandons a small child – at least in terms of emotional and social competence. During the first few scenes of Dear’s play, the newborn experiences the helplessness and vulnerability of early childhood. Shelley’s original similarly stresses the sensory confusion of the creature after birth (cf. 98f.) and its sense of wonder, delight and amazement at the world. The creature’s emotional and intellectual development come at an accelerated pace: he learns by observation and emulating behaviour, as well as through the study of literature and through direct interaction with people. His education leads him to question his own identity, seeking similarity with others and finding none. He sees himself as ‘united by no link to any other being in existence’ (Shelley 125) and is rejected by humanity for his monstrosity and difference. Consequently, he accepts the role of inhuman, acting violently due to the unbearable pain of exclusion.

We feel sympathy for the creature, because its status as monster is culturally forced upon him. He is excluded because he is not seen as human, not granted the same status as others around him. His rage is a response to this social isolation.[4] His worth is defined only as a scientific experiment, a means to further Victor’s notion of mastery over nature. ‘How dare you sport thus with life?’ (Shelley 95) the creature asks: Shelley does not grant an answer, but Dear allows Frankenstein to voice his arrogance: ‘To prove that I could! … In the cause of science! You were my greatest experiment – but an experiment that has gone wrong. An experiment that must be curtailed!’ (38)

Elsa and Clive’s relation to Dren starts from a similar vantage point: they both claim the right to create life, simply to ‘prove that they can’. Frankenstein’s creation is fully grown, but Dren starts out as an embryonic form and evolves through the human stages of infant, child and adolescent physically, emotionally and intellectually. Due to its sf premise, the film is able to overtly engage the parenthood-science allegory. As one critic points out, this leads to many moments of parental shock: ‘Dren’s rapid growth gives the couple all the pain and even some of the joys of parenthood’ (‘Splice, the Twisted Family’). Importantly and in contrast to Frankenstein’s creature, Dren is not neglected, not treated with rejection and human cruelty but with a growing love and compassion; she is not driven to violence, not denied ‘human’ subjectivity. In most scenes, the film presents Dren’s development and Clive and Elsa’s reactions to it as shifting between the poles of raising a child and conducting scientific research on animal intelligence.

As Dren grows, many typical situations of child rearing find an unusual expression in the experiment. For example, when the splice needs to be fed, Clive and Elsa approach the problem of nutrition rationally. They put together a nutritional pulp and try to feed Dren (still called H-50) with a baster, all the while documenting their progress. It is not explicated in the film, but the script states the scientific orientation of the diet: ‘We’ve got H-50 on a diet of chlorophyll, roughage, bean curd, and enriched starch’ (Natali et al. 37). Taste is not a relevant factor and, understandably, Dren rejects the food pulp, spitting out the mushy green stuff, screeching loudly and fighting the feeding process, just as a baby most likely would. Clive’s reaction reveals his inability as parent, the complete helplessness towards his ‘subject’ and the unexpected pressures the illegal experiment exert on him. He is irritated and repulsed by the feeding, clearly uncomfortable in his role: ‘This isn’t going to work. She makes too much noise. People are going to notice. And she stinks’. Clive and Elsa find the solution by accident, when Elsa’s candy spills all over the floor and Dren eagerly gathers it up. In the end, the inapt scientists need to resort to the same tactics that many parents (as well as pet owners) have used before them. Elsa mixes the candy into the nutritional pulp and offers the sweetened mush to the splice. Dren sniffs, unsure of the pulp, but then buries her head in the bowl and eats heartily. In Clive’s scientific jargon, the solution is entered into the experiment log: ‘Tracking her feeding habits, we have determined that the H-50 craves high sucrose food stuffs’.

Later, Elsa uses the same candy to positively reinforce correct answers during Dren’s cognitive training, when she has to identify objects with abstract representations. This is reminiscent of training animals, and when documenting the process Elsa’s voiceover clearly follows the pattern of a scientific progress report: ‘Early cognitive recognition tests indicate a growing intelligence. Still, her mind remains her greatest mystery’. When Elsa discovers that Dren can also associate symbolic representation (written language), she does not scientifically record the results of that experiment but rather reacts as if her child just uttered its first word (which strangely enough it did, just not verbally) and is full of parental pride and joy. At this point, Elsa’s growing acceptance of her emotional relation to Dren is contrasted with Clive’s attempts at scientific distancing. The ethical judgment has switched. It falls to him to uphold scientific neutrality, scolding Elsa for letting Dren out of the lab: ‘Specimens need to be contained’, he argues. Elsa is abhorred and exclaims, ‘Don’t call her that! … Her name is Dren’. Elsa exhibits strong emotions, even motherly love. She clearly cares for and protects her child with all the fervour of a young mother: ‘Do you think they could really look at this face and see anything less than a miracle?’

What both scenes make clear is that there is no ‘proper’ protocol to follow. Everything about the H-50 experiment is categorically unstable. Neither the rules of parenting nor those of scientific conduct fully apply to the situation, and Clive and Elsa shift between roles. They are clearly incapable of policing the boundaries between experiment and childrearing and are consequently desperately overextended in both aspects. In addition, Clive and Elsa struggle with the economic and logistic pressures of their experiment. The risk of discovery become obvious when Dren attacks Clive’s brother when he accidentally hears Clive and Elsa arguing and sneaks into the storage room that Dren claims as her habitat. The immediate threat is defused, but it becomes clear that Dren needs to be kept in a bigger and more remote facility, where there is less possibility for corporate interference.

Before everything is ready for the planned move, Dren suddenly develops a fever and pushes the parents/scientists into a panic. They are unable to go to a hospital and insecure about the normalcy of any physical parameter for the hybrid. Mustering a moment of scientific rationality, Clive suggests a cold bath to draw the fever out. When the shock of the cold water sets in, Dren reacts violently with a seizure, her respiratory system collapsing. The scene is frenzied, using shaky, unusual and obstructed shots to reveal the complete unpredictability of the action and the unknowable results (an overhead shot from above a bouncing lamp, followed by a medium shot of Dren being carried, then an underwater shot from the tub into which she is lowered). The camera keeps moving around the static characters, trying to find angles through the obstruction but no clear shot of Dren emerges. The panic finds its high point when Dren seems to suffocate. A low-angle shot of Clive breaks the pace. The sound fades, and the camera zooms in on his face in an extreme close-up of him breathing in before deciding to act. He grabs Dren’s stinger and pushes her under water with the other hand – at this point it seems to the viewer (as it does to Elsa) that Clive wants to kill Dren. Elsa screams in desperation, fighting Clive who keeps holding Dren underwater. Frantic camera movement and fast-paced cuts convey the snap decision and unpredictability of the situation. In the end, Dren seems to die, silence and lack of movement indicating the struggle to be over, before she breathes through her amphibious lungs.

Elsa is baffled: ‘You saved her, how did you know? … You knew, right?’ Clive’s hesitation and the close-up shot on his face, struggling with the consequences of his actions, leave lingering doubt about his motivation. The child/the experiment certainly threatens him, and ending Dren’s live would have been an easy option. The scene reveals the internal debate within the couple regarding how to deal with the effects that Dren has on their lives. Interestingly, the film never indicates how or why the mutation was triggered, but the concurrency of the direct threat of discovery (high stress levels) and the mutational burst suggest Dren is finely attuned to changes in her surroundings and reacts both physically and psychologically to them.

When Clive and Elsa finally need to hide Dren more effectively, they take her to the abandoned farm of Elsa’s youth. Dren once again becomes stressed, resisting being brought into the barn, and escapes their custody. She runs off, both escaping confinement and expressing her curiosity for the new environment. When they find her, she has hunted a rabbit and eats it raw – smiling innocently with blood covering her face and her hands full of entrails. Unable to accept Dren’s predatory, animal side – or in parenting terms, her defiance – Elsa imposes her own (human) values and norms on Dren: ‘That was bad. Bad Dren!’. Cinematographically, the film seems to undercut this motherly superimposition: Dren stands in the hayloft, elevated by at least 12 feet, her back to Elsa, who needs to crane her neck and is distant from Dren. The camera keeps the focus on Dren, shown in close-up, pondering the scolding she receives with more curiosity then remorse. The light is also solely on Dren, Elsa’s position in the frame is diminished by the long focus and the darkness in which she stands. Adding irony to the scene is Elsa’s jacket, which displays a white bunny on its lapel, right above her heart – involuntarily marking Elsa as prey, foreshadowing that the power dynamics will turn. This is even further emphasised when Dren does not accept the human care of a blanket, and in a very aggressive and sudden move jumps from the hayloft to a large tank of water, where she can remain alone thanks to her amphibious nature.

Similar to Frankenstein’s creature, Dren learns from observation and emulation, but in her case the exclusion from humanity is more subtle: she discovers a box of Elsa’s childhood things and realises her separation from her ‘parent’. Like Frankenstein, Splice enacts physiological difference as a marker of exclusion: in Dren’s case, Elsa’s long blonde hair is singled out as a feature that biologically connects her to other humans and her family. The hairless Dren is excluded from this connection and by extension from humanity. She finds a tiara and places it on her head, looking in the mirror and confused about the tiara’s purpose. Then she discovers the photograph of Elsa as a child, held by her mother. Their embrace and their similar long, blond hair that seems to flow from mother to daughter in a straight line where their heads touch enhance the strong family resemblance. Lastly Dren discovers a Barbie doll with long blond hair, touches it and then holds the doll to her face, stroking the blonde hair against her cheek. Her look is longing, the framing of the shot (mostly presented in the mirror image) reveals her helplessness in the situation. Dren, like Frankenstein’s creature, realises her exclusion from humanity because of her physiology. Even though her parents do not reject her overtly, Dren is nevertheless kept a secret, hidden from other humans and excluded from society. Moreover, the scene has a double, echoing a scene from earlier in the film in which Elsa took out the same childhood keepsakes after Dren had awakened her motherly side. Elsa seems fond of the keepsakes but also deeply saddened by the memories they evoke, and she also strokes the doll’s hair. Dren’s reaction to family is thus a close mirroring of Elsa’s – revealing that both lack familial connection, lack the love and security of a stable parent.

With Dren’s growing needs for movement, interaction and emotional relation, Clive and Elsa’s motivations and attitudes towards Dren change. Elsa had strong motherly feelings as long as Dren was small, but they fade as she feels as if she is losing control of Dren. After Dren demands freedom by spelling ‘tedious’ and ‘outside’ with Scrabble tiles and overthrowing the table. Elsa becomes overbearing, aggressively pushing Dren into the role of inferior: Dren feels rejected and is stressed. She escapes to the roof of the barn, where Clive and Elsa follow and are forced to balance across the gable of the barn – needing to tread lightly or risk slipping. The scene literalises the metaphorical challenges of dealing with an adolescent child. When Elsa barks an order, Dren looses her foothold and falls of the roof. Misplaced authority and control are fatal to their relationship and the stress triggers another mutational burst as wings and a back ridges sprout from Dren’s body. Her face, shown in close-up, reveals that she is completely unaware of her own potential and that the mutation comes as a gift to her. The next cut shows a long shot of Dren on the roof in profile, spreading her wings and straightening her posture as she realises her power – again a literal representation of the metaphorical change. She turns around and is about to fly from her captors, when Clive takes on the role of caring parent and diffuses the situation by telling the insecure, emotionally unstable Dren what she needs to hear: ‘Dren, we need you. … Dren, we love you’.

The rather blunt teenage attempt to break from parental supervision makes obvious that Clive and Elsa have lost control, both in terms of their scientific experiment (which shows cognitive and physical abilities that go beyond their expectations) and in terms of parenting (Dren’s power to simply fly away). The cascading needs of the experiment leave Clive and Elsa helpless and their panicked search for solutions ultimately results in abuse and violence. After another rebellious outburst, parental control fails and Dren attacks Elsa, who then fully reverts to a scientific position, reclaiming control over her experiment. Just like Frankenstein, she exercises her ‘right’ to curtail the experiment, using life as sport. She determines that the girl she has raised might be ‘misbehaving’ due to a ‘disproportionate species identification’ and that Dren needs to be de-humanised. Elsa captures and restrains Dren, psychologically humiliates her (by forcefully removing her clothing), and even physically maims her by cutting off her stinger (which has been revealed to be a weapon), all in the name of science and a desperate need of control. Elsa replays the abuse she received from her own mother and thus continues the cycle.

Elsa’s drastic act of parental transgression is not the only one. After having witnessed Clive and Elsa’s sexual intercourse, Dren starts to show sexual desire for Clive, which he tries to resist but ultimately reciprocates. In an intimate moment, showing Dren how to dance, he becomes enraptured by her. The camera captures his loss of orientation by following the revolving motion of the dance, providing extreme close-ups of Dren’s neck and slowing down the action. Clive jolts back into reality with the dawning realisation that Elsa has used her own DNA for the splice and that he is falling for Elsa in Dren.

When Elsa abuses Dren, Clive feels compelled to soothe Dren. Elsa and Clive fight, and he stays on to watch over Dren, who tries to seduce him. After reprimanding her (‘No, you can’t do that!’), he sees her shame as well as her desire for him. He cannot resist (he keeps repeating ‘can’t do that’ to himself) and finally gives in. The scene is extremely disturbing in its complex possible implications of incest, paedophilia, bestiality and ethical breach. Nonetheless, the emotional connection seems genuine: the scene is erotic and does reveal Dren’s sexual development, her status as adult. In a provocative shot – Clive lies on the floor, Dren straddles him, the camera is positioned on the floor, giving us a semi-subjective view of Dren close to Clive’s perspective – we see Dren literally becoming adult by extending her arms and fully unfolding her wings and back ridges, later even re-growing the castrated stinger. The scene is empowering and shows Dren fully in control, having outgrown the experiment and her parents, replacing Elsa and taking Clive as lover.

Elsa and Clive later realise their ethical transgressions, that they have failed on too many levels. Both come to the conclusion that their relationship to Dren as parents is broken, but instead of facing up to their actions they revert to their view of Dren as scientific experiment. They believe there is a solution to the situation, once viewed with detachment: ‘The experiment is over, responsibilities end’. But of course responsibility does not end, because the scientific experiment is just as fraught with ethical conundrums. Just as Frankenstein had to pay the price for his hubris, so do Elsa and Clive, when the next mutational cycle in her evolution begins.

The origin and parameters of Dren’s mutational cycles are not explicitly discussed in the film, but they do seem to conform to periods of extreme stress that are triggered by external stimuli. Further, they sometimes seem to involve a state of death-like rest, in which her body literally shuts down before a radical mutational burst (i.e., her ‘drowning’ before activating the amphibious lungs). In a sense then, her existence is connected to death, enhancing the resemblance to Frankenstein’s creature. Furthermore, the changes are symbolic of the unpredictability of scientific experimentation. Just as Ginger, the female transgenic organic becomes male near the film’s beginning, an event so unexpected the scientists have to abandon the H-40 splices altogether, H-50 (Dren) is not a controlled experiment with calculable risks and reliable projections.

Consequently, after having made the transition to adulthood through sexual development, Dren’s body seems to initiate another mutational change. This time, the physical change is so massive that the death-like state period is extended. Clive and Elsa return to the barn and find her dying. They bury her and start cleaning up the barn. Unknown to them, Dren emerges changed, having switched biological sex and becoming much more aggressive, territorial and predatory in the process. In the final conflict, triggered by the corporation arriving and trying to establish authority over its property, the new male Dren reacts as if threatened. He first eliminates all perceived threats, i.e. all other males who might challenge his dominance over the territory. In the final battle between Dren and the scientist couple, he kills Clive with a final blow from the stinger, re-enacting Frankenstein’s loss of his wife Elizabeth. Elsa consequently becomes both prey and mate. Dren stalks and rapes her, before she manages to kill him.

Conclusion

Splice thus reveals an aspect of the Frankenstein myth that has long been neglected in many of its cinematic adaptations. Scientific experimentation comes with unpredictable challenges and unexpected consequences for the creator, and in that it resembles parenthood. In experimenting with protean, self-organizing and adaptable life, science is challenged and changed. Dren represents zoe – chaotic, forceful and ever-adaptive life – and forces her creators to change, adapt and evolve too. The film challenges the position of neutrality and detachment in science: Dren is human/animal, life/death, male/female, natural/artificial, amphibian/avian/mammal – but above all she is change and evolution.

The film literalises the correlation and interconnection between science and its living subject (zoe). As much as Clive and Elsa would like to demonstrate the cold and emotionally detached stance of science, dealing with Dren evokes a familial care and love. In a sense, then, Splice is an ideal representation of biohorror in that it does not focus on what went wrong (as does Frankenstein, blaming the scientist’s transgression of natural boundaries and neglect of the creature), but ‘is caught between a genuine fear of the bioethics of emerging biotechnologies, and a perplexed curiosity about what exactly can be done to the body with such technologies’ (Thacker 113). Splice thus enacts the posthuman as threatening, revealing the categorical crises produced by genetic engineering. In transporting the Frankenstein mythology into the 21st century, Natali thus comments on the unpredictability of genetics and the price to be paid if science has the hubris to claim otherwise.

More interesting though, is the fascination that Splice evokes when it challenges our notion of familial relation and the consequences of transgression. It seems necessary to point out that the Frankenstein character, Elsa, does not die for her hubris. Instead, the creature dies – but not before conforming to the instrumentalisation of its biology through technoscience. Dren functions too well in that Newstead’s investment not only remains intact but marketable products exceed expectations. As challenged as both scientists have been in dealing with the experiment, the emotional bonds with Dren somehow compel Elsa to continue. The film reclaims both Frankenstein and his creation from the moral fault line of good and evil. Splice enacts science as caught in a complex system of responsibilities, challenges and pressures that a new generation of scientists will need to navigate if they wish to engage in genetic engineering. The film explicates both the fascination and the fears of biological technoscience and thus promotes a critical engagement with these technologies and their consequences. In that, Splice helps us to come to terms with biotechnology’s role in our lives, and thus is a function of the ‘prime concern of sociology’ today, as Zygmunt Bauman has remarked: ‘individual self-awareness, understanding and responsibility’ (213).

Works cited

Allen, Glen Scott. Master Mechanics & Wicked Wizards: Images of the American Scientist as Hero and Villain from Colonial Times to the Present. Amherst: U of Massachusetts P, 2009.

Attebery, Brian. ‘Science Fiction and the Gender of Knowledge’. Speaking Science Fiction. Ed. Andy Sawyer and David Seed. Liverpool: Liverpool UP, 2000. 131-43.

Baldick, Chris. In Frankenstein’s Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth–Century Writing. Oxford: Clarendon, 1987.

Bauman, Zygmunt. Liquid Modernity. London: Polity, 2000.

Braidotti, Rosi. The Posthuman. London: Polity, 2013.

Captain. ‘Splice, Neuromancer and High Rise: The Twisted Future of Vincenzo Natali’. SFTV.com. Blog. 18 Aug 2010. Accessed 12 Dec 2013. <http://www.sftv.com.au/news/2010/08/splice-neuromancer-and-high-rise-the-twisted-future-of-vincenzo-natali/>

Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome. ‘Monster Culture (Seven Theses)’. Monster Theory: Reading Culture. Ed. Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1996. 3–25.

Dear, Nick. Frankenstein. Dir. Danny Boyle. Writ. Nick Dear. Perf. Jonny Lee Miller, Benedict Cumberbatch. Opening: 5 Feb 2011.

Dinello, Daniel. Technophobia: Science Fiction Visions of Posthuman Technology. Austin: U of Texas P, 2005.

Dougherty, Carol. Prometheus. London: Routledge, 2006.

Feineman, Neil. Geek Chic: The Ultimate Guide to Geek Culture. Amsterdam: BIS, 2005.

Haynes, Roslynn D. From Faust to Strangelove: Representations of the Scientist in Western Literature. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1994.

Herbrechter, Stefan. Posthumanism: A Critical Analysis. London: Bloomsbury, 2013.

Hustis, Harriet. ‘Responsible Creativity and The “Modernity” Of Mary Shelley’s Prometheus’. Studies in English Literature, 1500–1900 43.4 (2003): 845–58.

Inness, Sherrie A. ‘Introduction: Who Remembers Sabrina? Intelligence, Gender, and the Media’. Geek Chic: Smart Women in Popular Culture. Ed. Sherrie A. Inness. New York: Palgrave, 2007. 1–10.

Ku, Chung-Hao. ‘Of Monster and Man: Transgenics and Transgression in Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake’. Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies 32.1 (2006): 107–33.

Natali, Vincenzo. ‘Behind the Scenes’. Splice. BluRay. Universum Film, 2010.

Natali, Vincenzo, Antoinette Terry and Doug Taylor. ‘Splice’. Screenplay. Toronto: Copperheart Entertainment, 2007. Accessed 14 Jul 2014. <http://www.joblo.com/scripts/splice.pdf>.

Romney, Jonathan. ‘Splice, Vincenzo Natali, 104 Mins (15)’. The Independent. 25 Jul 2010. Accessed 10 Aug 2010. <http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/reviews/splice-vincenzo-natali-104-mins-15-2034657.html>.

Schmeink, Lars. ‘Biopunk Dystopias: Genetic Engineering, Society and Science Fiction’. Dissertation. Humboldt University Berlin. Institute for British and American Studies. Berlin, 2014.

Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. 1818. London: Penguin, 1994.

Small, Christopher. Ariel Like a Harpy: Shelley, Mary and Frankenstein. London: Gollancz, 1972.

‘“Splice”, the Twisted Family Sci-Fi Horror Film Made of Awesome’. Blastr.com. 4 Jun 2010. Accessed 14 Jul 2014. <http://www.blastr.com/2010/06/splice_makes_all_other_sci_fihorror_mash_ups_look_lame.php>.

Thacker, Eugene. ‘Biohorror/Biotech’. Paradoxa 7.17 (2002): 109–29.

Wolfe, Cary. What Is Posthumanism? Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2010.

[1] Splice is a multi-layered and fascinating film that allows for a variety of readings. There is its contribution to Canadian film, especially the horror genre that has grown in reputation and originality since the success of John Fawcett’s Ginger Snaps (Canada 2000), for which Natali incidentally worked as storyboard artist. The film has a complex production history speaking to the difficulties of financing and producing small, independent sf films. A psychoanalytical reading of the film, with its adolescent turmoil and enactments of both Electra and Oedipus complexes, would also be fruitful. Further approaches might include a posthumanist reading, exploring the film’s Gothic motives (especially in its set design), and its rich intratextual tapestry, especially its filmic genre precursors in James Whales’ Frankenstein films: the protagonists, Clive and Elsa, are named for actors Colin Clive and Elsa Lanchester, who played creator Henry Frankenstein and the monstrous bride respectively.

[2] I refer to the posthuman as an entity created through technoscience, that surpasses the human both chronologically (‘after the human’) and in its abilities (‘beyond the human’); For a detailed analysis of posthumanism as critical theory cf. Braidotti, Herbrechter, Wolfe; for posthumanism in Splice cf. Schmeink.

[3] Ginger and Fred are obviously named for 1930s Hollywood stars Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire, whose on-screen romances made them an iconic couple.

[4] It is ironically fitting that most film versions in the 20th century, with the notable exception of Kenneth Branagh’s Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein(1994), deny the creature a voice and stereotype him exactly as the brutish monster that humanity sees in him. His mistreatment and the resulting justification for rebellion are thus made invisible.

Ursprünglich erschienen in Science Fiction Film and Television – PDF

Schmeink, Lars. „Frankenstein’s Offspring: Practicing Science and Parenthood in Natali’s Splice.“ Science Fiction Film and Television 8.3 (2015): 343-69.