The Queer Community Protopia of Ace in Space

This talk was originally given at the 13. Jahrestagung der Gesellschaft für Fantastikforschung – Fantastic Geographies – at the TU Dortmund on Sep 22, 2022. Here is a recording to listen to or the text to read along my slides.

At a roundtable discussion on „Embodiment and Science Fiction“ a few weeks back, author and scholar Jo Walton said that those of us who deal in science fiction have the obligation to call out and criticize the kinds of techno-utopias that are currently being peddled as solutions to climate change and social unrest. They are not solutions, they are continuations of the problem. And I agree. Silicon Valley and its hypercapitalist ventures will not save the planet from destruction and they will not make our lives better. They will entrench the colonial and extractive thinking that is driving our current economy. They will deepen the social divides and uphold a racist, mysogynist and otherwise marginalizing and oppressive system. If that is what utopia represents today, then it is not worth pursuing.

A similar thought occurred to Wired founding editor Kevin Kelly back in 2011, when he claimed that neither utopia nor dystopia could provide a realistic vision of the future that was both „plausible and desirable“ and thus worth working for. And because of that, he argues, we are „future-blind“, meaning we are stuck in the present, avoiding the long view. He calls his solution to this problem: Protopia. „Protopia is a state that is better than today than yesterday, although it might be only a little better. Protopia is much much harder to visualize. Because a Protopia contains as many new problems as new benefits.“

Ten years later, futurist and designer Monika Bielskyte has picked up the terminology and expanded it. She published a framework for thinking about „radically hopeful and inclusive future ways of seeing and being in this world“ – and though I refer to her as if she were the single author of this framework for convenience, I want to express here that it is based on collaborations with a variety of people all named on the website. But Bielskyte is the face of this movement and she published it under her Medium-Account. So … to Bielskyte, then, Protopia is more radically wholistic and more centered on social justice. She argues that we need to address the systemic wrongs of our past and present and „replace them with regenerative and equitable alternatives“ instead of looking for techno-patches to the next emergency. One important aspect to this political and activist endeavor is to imagine these Protopian future pathways and to think on them creatively.

In the following, I want to argue that the German progressive fantastic, inaugurated by James Sullivan and Judith Vogt has a similar, Protopian, outlook. Sullivan and Vogt are looking to move genre writing towards a reflection of a better society. There is a distinctly activist undertone, when they call for the fantastic to be representative of a socially just and culturally diverse society. They are interested to use the fantastic as a means to think about progressive politics and social equality. For them certain narrative traditions can be „in the way“ of representing that reality, they can „block us, limit us, or even hurt us.“ Consequently, they call out to authors to break with these traditions and instead find new ways to imagine other worlds.

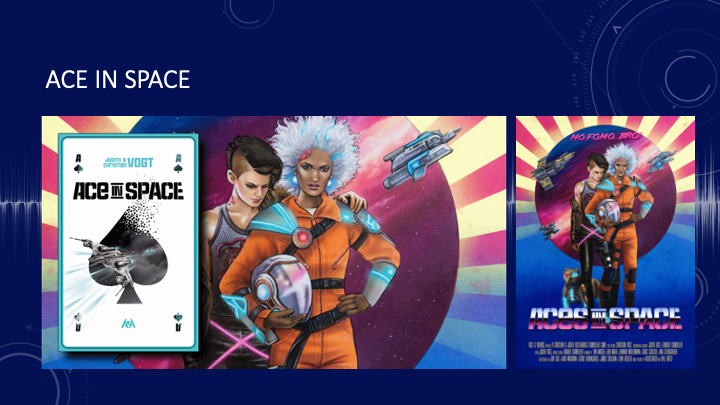

As an example of this progressive thinking, I want to read Judith and Christian Vogt’s Ace in Space as a creative imagination of a Protopian future.

Before going into a detailed analysis of the Protopian elements of the story, let me shortly recap. Ace in Space is a fun space-opera-inspired adventure story about a gang of anarchic space jockeys, the Daredevils. They hire out their choppers (i.e., spaceships) to anyone who is willing to pay for transport, security, a little pirating or smuggling, whichever is profitable. In order to stand out in the Kobeni asteroid belt, gangs like the Daredevils rely heavily on social media. Their prowess at flight stunts, shoot outs, and high speed chases is continuously presented via videos and commented upon by a fan base. They are a mix of space pirates, Jackass-type stunt people and youtube influencers.

The story revolves around a job for a group of independent settlers on Valoun II, who are being threatened by a conglomerate over their mining claims on the valuable resource Minconium. The conglomerate lays siege to the settlements, bombards them, and even uses a fanatic sect of mutants to attack the miners. The Daredevils help out as best as they can and start a campaign for social media attention and keep the miners alive with transport and firepower.

Out of the principles of Protopia that Bielskyte formulates, Ace in Space is an exploration of plurality and community. It is an an attempt of queering that moves beyond borders and binaries that sets up a Protopian view of community as the space for a radical and hopeful future. I will thus concentrate here on the two aspects of plurality and community to show how this progressive SF is Protopian …

Protopia’s first principle is „plurality“ and a strong stance against any form of exclusionary „categorization and discrimination“. Bielskyte makes clear that gender and sexuality need to be seen as fluid, that ethnic difference is a boon and that more and more people are touched by more than one culture. Protopia also embraces difference and plurality in terms of age and physical or mental abilities. Inclusion and acceptance of plurality thus become the key instrument of a Protopian future.

And Ace in Space provides just that. The communities presented in the novel are Protopian in their embrace of plurality. In terms of gender, for example, the novel presents non-binary characters not just as tokens but in every walk of life: there is a social media person Gingko, mine worker Noor, pilot Eyegle, judge Dawson. Sexuality is also fluidly represented as an „exploration space“, from bisexual to asexual characters, to concepts of „shipping“ which explore fantasies of seeing favorite media characters together, to object sex, when engineer Kami is „shipped“ with the slipstream fighter jet she is working on.

Beyond the level of content, the novel makes a concerted effort to present everything in non-heteronormative language. Judith and Christian Vogt use a queer linguistic repertoire to playfully explore how the German language can be de-gendered. They employ the neopronoun „xier“ for non-binary characters, adding also neologistic forms such as the x-suffix, such as „Vloggerix“ or „Mx“. The novel does not gender via generic masculine but uses the epicene term „person“ for different roles, such as with gravitas in „Richtperson“ (meaning judge_n), or light-heartedly as in the online user CowPerson Yeeha (instead of Cowboy). Further, the novel uses gender crossing and combines it with the use of English slang terminology of pilots and social media jargon. Terms like „President“ and „Jockey“ which remain English in German but are typically gendered masculine (both grammatically and socially) are here used with feminine inflection. In addition, Judith and Christian Vogt point towards accepted forms of gender splitting via the use of a colon in written language, as in Vorfahr:innen or Bürger:innen. These different strategies are employed in the text to playfully highlight that there are several options to eliminate heteronormative language and its use of binarism. Ace in Space shows how queer linguistics signal a future that is not dependent on a binary perspective on gender and sex but embraces a Protopian plurality even in its formal aspects.

And the novel does not stop at gender and sexuality for a queer plurality in representation. Using Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick definition of queer as „a continuing moment, movement, motive“ that works „across“ categories and is a „multiply transitive“ „open mesh of possibilities, gaps, overlaps, dissonances and resonances, lapses and excesses of meaning“ (7), the Vogt’s communities, explore a Protopian queerness by promoting an inclusive approach to any form of personal identity, in the intersectionality of ethnicity, gender, sex, (dis)ability, age, or mental health.

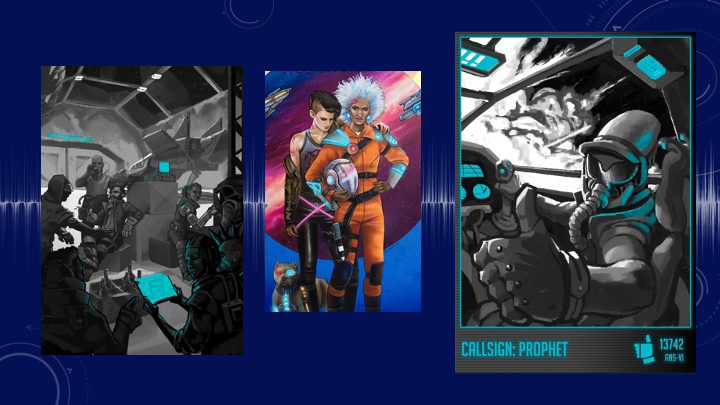

The Daredevils are a queer Protopian community. In terms of age, they range from the President Deardevil and Vice-President Garuda, two hardened middle-aged women, to teenage prospects waiting for their chance. As seen in these illustrations, taken from the accompanying roleplaying game, the characters are also ethnically diverse, as personified in the three protagonist: Fighter pilot Danai, aka Princess, is a black woman of mixed ethnic heritage, Neval is of Arabic descent with a muslim religious background, and prospect Kian, aka Prophet, is what the novel calls a „Navig“, a descendent of South Pacific Islanders who moved to the stars and who navigate its vast oceans like their ancestors did the Pacific. And lastly, the spectrum of bodily and psychological ability is also addressed. Through Danai, who is the bad-ass pilot protagonist, but also a stutterer suffering immense linguistic blockages in social situations. And through Amit, one of the settlers who is quadriplegic and leads the settlement of Amittown. The inclusion of plurality even extends to the posthuman with members of the squad having become cyborgs through implant technology like reflex boosters or specialized optical implants.

As has become clear, this plurality of individuals in the story and in Protopia becomes community. And this is the other important principle of a Protopian future imaginary. Community is a rejection of individualism, and thus of hero or savior figures. Instead, Bielskyte proclaims that Protopian futures should be stories of community building and how diversity makes a community stronger … and how Protopia builds on relationships not just between the diverse individuals but also between diverse communities.

In the novel, we can find this latter aspect in the mining communities, which work together against Hadronic, the people of Fervintown fleeing to Amittown and banding together. And it is found in the miner’s alliance with the anarchic space jockey gang. Both communities are diverse and very different to each other, yet they cooperate to fulfill the same goal – to beat the corporate conglomerate, which is exploiting the miners and the natural resources on the planet. The fight for freedom to live without overwatch and corporate exploitation.

When the mining communities come together to fight of the corporation and even employ the Daredevils they seek a communal solution. The conflict is not resolved in a large fight. Instead it is a rescue mission, keeping a community alive in a group effort – getting everyone to safety, providing resources to hold out the siege, and finally instead of a desperate last stance giving up the settlement and flying the settlers off to safety. And further, the solution to the conflict is won as much via resistance against the siege, fighting off attacks and fleeing before the violence, as it is via administrative and judicial methods – bringing a law suit before the corporate court system which ultimately restores the settler’s rights and position. Different skills from a diverse and pluralistic community are needed for the community to survive and rebuild.

There are other aspects of the novel that I would argue to be Protopian – how the story embraces indigenous rituals of the Pacific Islanders as valuable in connection to the faster-than-light technologies in a form of symbiotic spirituality and maybe also how the creative and emergent subcultural aspects of social media, video blogging and influencer lifestyles become artistic and activist weapons in the fight against the conglomerate. There is more to be developed here. But in general, I would argue that Ace in Space is a Protopian future imagined through the lens of the progressive fantastic. It is both imagination and activism in that it generates hope that a positive and more socially just society is possible. Not a utopia that sees all problems solved by technological intervention, but a Protopia that comes together around different progressive ideals … thank you very much.

Works Cited:

- Bielskyte, Monika. „Protopia Futures [Framework].“ Medium.org. May 18, 2021. https://medium.com/protopia-futures/protopia-futures-framework-f3c2a5d09a1e. Accessed May 9, 2022.

- Kelly, Kevin. „Protopia.“ KK.org. May 19, 2011. https://kk.org/thetechnium/protopia/. Accessed May 9, 2022.